Association of Unfavorable Social Determinants of Health With Stroke/Transient Ischemic Attack and Vascular Risk Factors in Hispanic/Latino Adults: Results From Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos

Article information

Abstract

Background and Purpose

Social determinants of health (SDOH) are non-medical factors that may contribute to the development of diseases, with a higher representation in underserved populations. Our objective is to determine the association of unfavorable SDOH with self-reported stroke/transient ischemic attack (TIA) and vascular risk factors (VRFs) among Hispanic/Latino adults living in the US.

Methods

We used cross-sectional data from the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos. SDOH and VRFs were assessed using questionnaires and validated scales and measurements. We investigated the association between the SDOH (individually and as count: ≤1, 2, 3, 4, or ≥5 SDOH), VRFs and stroke/TIA using regression analyses.

Results

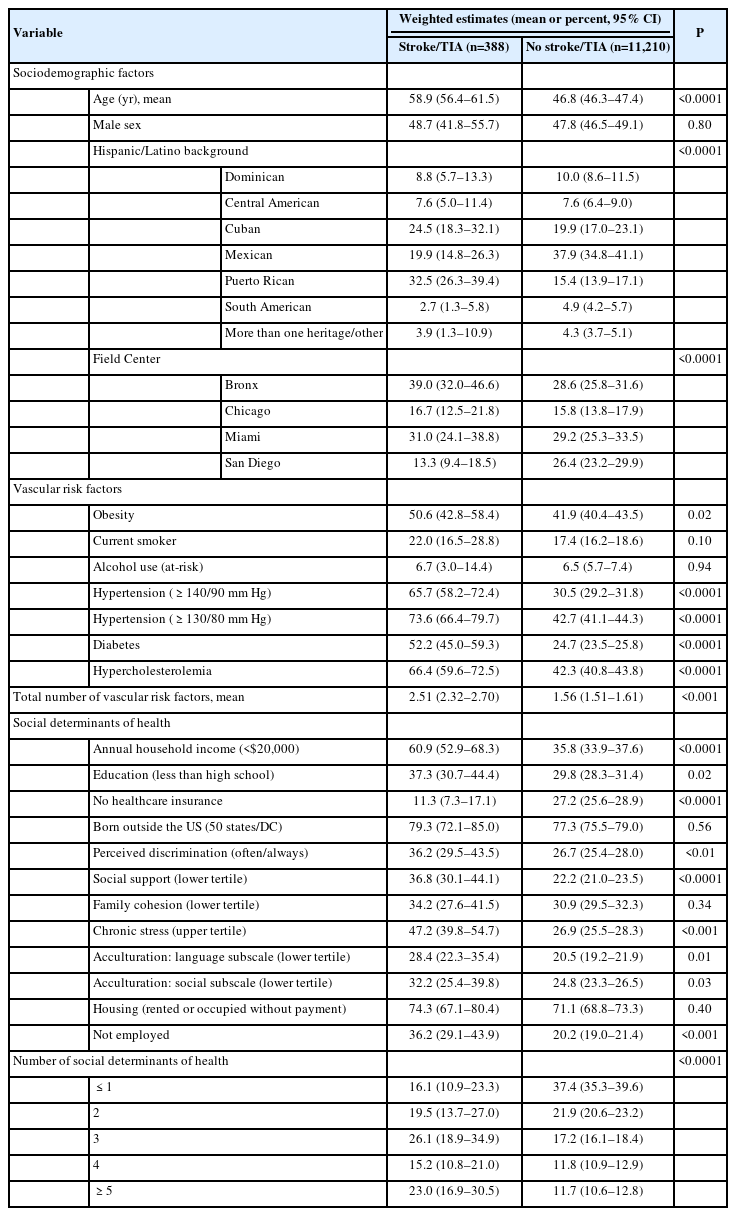

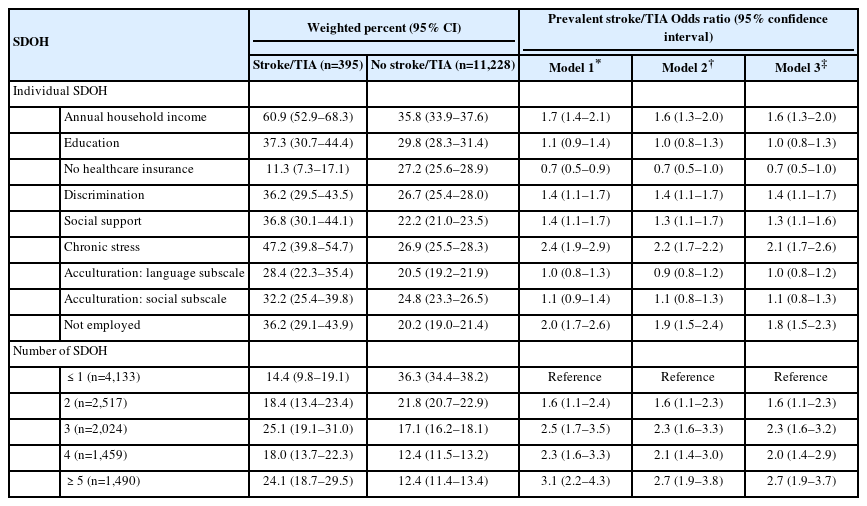

For individuals with stroke/TIA (n=388), the mean age (58.9 years) differed from those without stroke/TIA (n=11,210; 46.8 years; P<0.0001). In bivariate analysis, income <$20,000, education less than high school, no health insurance, perceived discrimination, not currently employed, upper tertile for chronic stress, and lower tertiles for social support and language- and social-based acculturation were associated with stroke/TIA and retained further. A higher number of SDOH was directly associated with all individual VRFs investigated, except for at-risk alcohol, and with number of VRFs (β=0.11, 95% confidence interval [CI]=0.09–0.14). In the fully adjusted model, income, discrimination, social support, chronic stress, and employment status were individually associated with stroke/TIA; the odds of stroke/TIA were 2.3 times higher in individuals with 3 SDOH (95% CI 1.6–3.2) and 2.7 times (95% CI 1.9–3.7) for those with ≥5 versus ≤1 SDOH.

Conclusion

Among Hispanic/Latino adults, a higher number of SDOH is associated with increased odds for stroke/TIA and VRFs. The association remained significant after adjustment for VRFs, suggesting involvement of non-vascular mechanisms.

Introduction

Stroke constitutes a leading cause of morbidity and mortality in the US and worldwide. The burden of stroke is particularly elevated among Hispanic/Latino adults, one of the fastest growing ethnic groups in the US [1]. Thus, it is critical to investigate the factors that contribute to stroke risk in this population. Unfavorable social determinants of health (SDOH) refer to adverse socioeconomic, cultural, structural, and policy-related factors that contribute to the development of illnesses through biological and/or emotional mechanisms [2]. Several SDOH, including job insecurity, low income, low levels of social support, and immigration status, have individually and collectively been associated with cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk [3,4]. In addition, SDOH disproportionally affect diverse populations that have historically been underrepresented in stroke research but are overrepresented in stroke risk and burden [4]. Thus, it is possible that SDOH may explain some of the stroke-related disparities noted in observational studies. The Reasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke (REGARDS), a population study of Black and White adults aged ≥45 years, observed a direct association between the number of SDOH and incident stroke risk [5]. This association, however, was only statistically significant for adults aged <75 years, with no statistically significant effects observed in individuals ≥75 years. Different mechanisms may explain this association. Unfavorable SDOH are associated with poor vascular risk factor (VRF) control such as restricted access to high-quality medical care and screening programs; lower compliance with medication use secondary to lack of insurance or access to local area pharmacies; and unhealthy behaviors (such as poor diet) secondary to residence in food deserts which have an abundance of convenience stores that sell unhealthy foods [4,5].

The Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos (HCHS/SOL), the largest and most diverse longitudinal cohort study of Hispanic/Latino adults living in the US, observed that SDOH, including a lack of structural social support, lower subjective social support, and housing insecurity are associated with poor cardiovascular health [6,7]. However, there is a paucity of information on the association of SDOH with prevalence of cerebrovascular injury in Hispanic/Latino adults. This study seeks to expand our knowledge in this area by investigating the association of unfavorable SDOH with stroke/transient ischemic attack (TIA) in a large cohort of community-dwelling Hispanic/Latino adults. In addition, we also investigated whether this relationship is associated with an increased VRF burden among individuals with multiple SDOH.

Methods

Study sample

This cross-sectional study utilized data from HCHS/SOL, a longitudinal, population-based study of Hispanic/Latino adults living in the US. The HCHS/SOL study design and rationale are available elsewhere [8]. Further details about the study can also be found here: https://www.clinicaltrials.gov (Unique identifier: NCT02060344). Briefly, between 2008–2011 (Visit 1), HCHS/SOL examined 16,415 self-identified Hispanic/Latino individuals aged 18–74 years, who were recruited from households selected using a multi-stage probability sampling design from four US communities (San Diego, Chicago, Bronx, and Miami) with oversampling of the population aged ≥45 years. Participants underwent a second examination between 2014–2017 (Visit 2; n=11,623). The average time between Visit 1 and Visit 2 was 6 years. The calculation of the sampling weights was based on characteristics at Visit 1 and accounted for nonresponse at Visit 2. Sampling weights were trimmed and calibrated by age, sex, and Hispanic/Latino background to the characteristics of the four sampled communities using 2010 US Census data. The study was approved by the institutional review boards at each participating institution. Written informed consent was obtained from all individuals. All variables and outcomes used in this study were queried at Visit 2, except when indicated otherwise.

Primary outcome

The primary outcome was prevalent stroke/TIA, defined based on self-reported history of stroke/TIA. This was ascertained by asking participants “Has a doctor said that you had a stroke, mini-stroke, or TIA?”

Exposure

For this study, we used the SDOH included in the PhenX toolkit [9] from the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities and the American Academy of Family Physicians EveryONE Project [10]. Included (and self-reported) SDOH were household income, attained education, healthcare insurance coverage, place of birth, discrimination (only available at Visit 1), social support, family cohesion, chronic stress, acculturation (language use and social subscales), housing, and employment status. Foreign-born status was defined as birthplace outside of the US 50 states/DC. Participants were considered “not employed” if they were not retired (or missing data on retirement) and not currently employed. Discrimination was assessed using a scale that evaluates how often unfair treatment, attributable to ethnicity, happened to oneself or others. Responses were recorded as never, sometimes, often, or always [11]. Social support was assessed using the 12-item Interpersonal Support Evaluation List, with scores ranging from 0 to 36 with higher scores reflecting greater perceived support [12]. Family cohesion was assessed using the 10-item cohesion subscale of the Family Environment Scale, with higher scores indicating higher family cohesion [13]. Acculturation was measured using a modified 10-item version of the Short Acculturation Scale for Hispanics with two subscales, language and ethnic social relations. The language subscale includes six questions regarding the preferred language (English vs. Spanish) for reading, speaking, thinking, and media use. The ethnic social relations subscale has 4 items that measure preference for the ethnicity of social contacts. Scores for each item range from 1 to 5, with higher scores denoting higher levels of acculturation to the US [14]. Chronic stress was measured with an 8-item self-report scale that assesses ongoing (past 6 months or more) exposure to psychological stress in important life domains, including work, relationship, finances, and health problems for self or family [15,16]. A total number of chronic stressors score was created based on the sum of events that participants answered affirmatively. Validation studies for the scales used have been previously reported [14,16-19]. The cutoffs used for each SDOH are outlined in Table 1. We calculated a count score of SDOH, with one point for each criterion met. Based on the distribution of SDOH counts, participants were categorized into one of 5 groups: ≤1, 2, 3, 4, and ≥5 SDOH.

Covariates and secondary outcomes

Sociodemographic variables included age (in years), sex, and Hispanic/Latino background. Participants in the HCHS/SOL self-identify their background (or their families) as Cuban, Dominican, Puerto Rican, Mexican, Central American, or South American. Obesity was defined as a body mass index ≥30 kg/m2 and at-risk alcohol use as >2 drinks/day for men and >1 drink/day for women [20]. Smoking (current smoker) was self-reported. Prevalent hypertension was defined as blood pressure >140/>90 mm Hg or on treatment, as recommended by the American Heart Association secondary stroke prevention guidelines in use at the time of data collection [21]. The 2017 American Heart Association guidelines for hypertension management introduced the blood pressure goal of ≤130/≤80 mm Hg [22]. Thus, the data were also analyzed using this threshold. Blood pressure was measured with the individual in the seated position using an automatic sphygmomanometer. Three blood pressure measurements were obtained 1 minute apart, and the average of these three blood pressure values was used in this analysis. Prevalent hypercholesterolemia was defined as fasting total cholesterol ≥240 mg/dL, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol ≥160 mg/dL, or on treatment. Prevalent diabetes mellitus (DM) was defined as fasting plasma glucose ≥126 mg/dL, 2-hour post-load plasma glucose ≥200 mg/dL, glycosylated hemoglobin ≥6.5%, or on treatment.

Analytic plan

All analyses accounted for the complex survey design of HCHS/SOL (clustering and stratification) and sampling weights were used to adjust for the unequal sampling probability and nonresponse. Descriptive characteristics and prevalence rates for SDOH by self-reported stroke/TIA status were estimated using linear and logistic regression models. SDOH found to be associated with stroke/TIA in bivariate analysis (P<0.05) were retained for further analyses. Missing data were handled by multiple imputation based on the fully conditional specification model. We investigated the association of history of self-reported stroke/TIA and SDOH (individually and SDOH count) using logistic regression models. In model 1, pairwise comparisons were done by using SDOH group 1 as the reference and adjusting for age, sex, Hispanic/Latino background, and field center. Model 2 was further adjusted by VRFs with a P<0.05 in univariate analysis. The final model was adjusted for age, sex, Hispanic/Latino background, field center, obesity, hypertension, DM, hypercholesterolemia, and number of VRFs (model 3); odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) are reported.

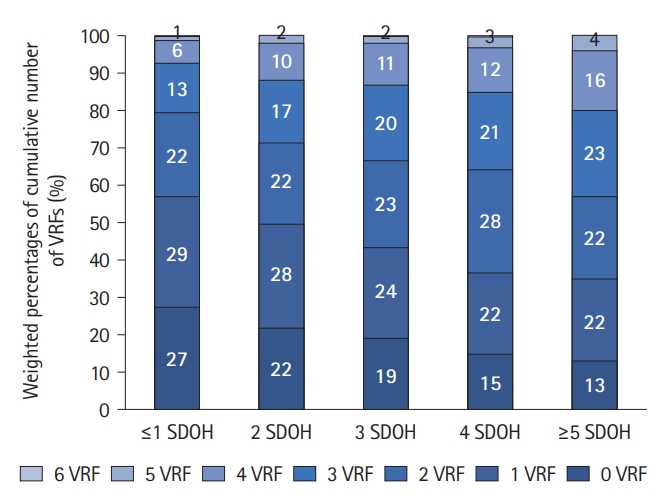

Since VRFs are highly associated with stroke/TIA, we also determined the overall association between each VRF and number of SDOH using linear regression analysis. We then tallied the number of VRFs and graphed the weighted percentages of the total number of VRFs for each SDOH group. A predictive regression model was used to investigate the association between the VRF count and SDOH group (i.e., ≤1, 2, 3, 4, and ≥5 SDOH) as a continuous variable while adjusting for age, sex, field center, and Hispanic/Latino background. The resulting β coefficient represents the average change in the mean of the total number of VRFs per each SDOH group change. Analyses were performed using SAS software version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Out of all 11,623 participants, 99.8% had self-reported stroke/TIA history available and 92.7% had data available for at least11 of the 12 SDOH used in this study. Table 2 depicts the baseline characteristics of our sample. Individuals with self-reported stroke/TIA had higher mean age than those without such history (58.9 vs. 46.8 years, P<0.0001) and a higher prevalence of hypertension, DM, hypercholesterolemia, and obesity. Participants with self-reporting stroke/TIA had higher frequencies of income <$20,000, education less than high school, no health insurance, perceived discrimination, not retired and not currently employed, were in the upper tertile for chronic stress and in the lower tertiles for social support and language- and social-based acculturation. These SDOH were used in further analysis.

Table 3 depicts the association between individual SDOH and number of SDOH with prevalent stroke/TIA. Increasing number of SODH (max=9) was associated with higher odds of stroke/TIA. In model 1, the odds of stroke/TIA were 2.5 times higher in persons with 3 SDOH (95% CI 1.7–3.5) and 3.1 times higher in those with ≥5 SDOH (95% CI 2.2–4.3), compared to those with ≤1. This association persisted after adjustment for additional covariates (model 3). In our final model (model 3), income <$20,000, perceived discrimination, lower tertiles for social support, upper tertile for chronic stress, and not being currently employed were individually associated with higher odds of self-reported stroke/TIA. A higher number of SDOH was associated with prevalent hypertension, DM, hypercholesterolemia, obesity, and smoking (Supplementary Tables 1 and 2). Compared to individuals with ≤1 SDOH, those with ≥5 SDOH had higher odds of hypertension (OR=1.5, 95% CI 1.3–1.7 for hypertension defined as blood pressure >140/90 mm Hg; OR=1.3, 95% CI 1.2–1.5 for hypertension defined as blood pressure >130/80 mm Hg), DM (OR=2.0, 95% CI 1.7–2.3), hypercholesterolemia (OR=1.4, 95% CI 1.2–1.5), obesity (OR=1.4, 95% CI 1.2–1.6), and smoking (OR=2.2, 95% CI 1.8–2.6). The distribution of the total number of VRFs varied by number of SDOH. Among individuals with ≤1 SDOH, 27% had no VRFs and 13% had ≥3 VRFs. Conversely, among those with ≥5 SDOH, 13% had no VRFs and 23% had ≥3 VRFs (Figure 1 and Supplementary Table 3). In the linear regression model, the mean number of VRF increased by 11% for each additional SDOH group after adjusting by age, sex, field center, and Hispanic/Latino background (β=0.11, 95% CI 0.09-0.14).

Logistic regression analysis for the association of number of SDOH and risk of stroke/TIA (multiple imputation data)

Discussion

The results of our study demonstrate that among Hispanic/Latino adults, increasing number of SDOH is directly associated with prevalent stroke/TIA. In addition, five SDOH were individually associated with self-reported stroke/TIA, i.e., low income and unemployment, high levels of perceived discrimination and chronic stress, and low social support, after adjusting for demographic characteristics and VRFs. Increasing number of SDOH was also associated with higher odds of individual VRF, and total number of VRFs. However, the association between SDOH and stroke/TIA was independent of these VRFs. This suggests that non-VRF mechanisms, such as socioeconomic and cultural factors, may contribute to the higher burden of stroke/TIA noted in Hispanic/Latino adults. A wealth of literature demonstrates a strong association between SDOH and poor cardiovascular outcomes [23]. Although association does not imply causation, several mechanisms have been proposed to explain this relationship, including greater burden of VRFs, higher allostatic load scores, and stress-associated dysregulation of the autonomic nervous system [24,25].

Hispanic adults experience a greater burden of unfavorable SDOH including discrimination and socioeconomic adversity than non-Hispanic White adults. Thus, it is plausible (and our results support) that SDOH, such as living below the poverty line, having fewer years of education, and lack of health insurance or access to a healthcare provider [4,26], contribute to the elevated prevalence of self-reported stroke observed among Hispanic/Latino communities even after controlling for their VRF burden. In bivariate analysis, we observed that nine of the SDOH were more prevalent among persons with a self-reported stroke/TIA, compared to those without. These included low household income, education, and lack of employment, which are all indicators of socioeconomic status (SES) [4]. Low income and lack of employment remained independently associated with stroke/TIA after adjustment for confounders. The relationship between SES and CVD has been established in several studies [4]. In the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA), specific neighborhood characteristics indicative of SES were associated with incident HTN and DM [27,28]. In addition, in HCHS/SOL, Hispanic/Latino adults with unfavorable SES, defined as lower income or education [29], low perceived social status [30], and living in foreclosure risk areas [6], had worse cardiovascular health. Our understanding of the relationship between SES and stroke incidence and prevalence is evolving. In REGARDS, low annual household income and education were associated with incident stroke [5]. Similarly, in the Northern Manhattan study, a longitudinal study of 3,298 participants (52% Hispanic/Latino adults), low income was associated with incident stroke [31]. Data obtained in non-Hispanic/Latino cohorts show that individuals with low income who are diagnosed with stroke are less likely to be admitted to a stroke unit, receive antithrombotic agents, and receive assessment by physiotherapist or occupational therapy [32]. Thus, it is plausible that lack of access to high-quality care may contribute to the association between SES and stroke.

Chronic stress and discrimination are prevalent among Hispanic/Latino adults living in the US [17]. Discrimination has been linked to adverse CVD risk [23,33]. In addition, chronic stress has been associated with poorer glucose regulation and hypertension [34,35]. Despite these associations, the relationships among discrimination, chronic stress, and stroke among Hispanics/Latinos have not been completely described. In a previous study in HCHS/SOL, chronic stress was associated with prevalent stroke. However, this association was not retained after adjustment for VRFs [36]. These results, however, should be interpreted with caution as there was a small number of participants with prevalent stroke (n=77). In our final model adjusted for demographic characteristics and VRFs, chronic stress and discrimination were associated with higher odds of self-reported stroke/TIA. Our findings on chronic stress are consistent with a meta-analysis of 14 studies done in non-Hispanic cohorts, which reported that perceived stress was associated with a 33% increase in the hazard ratio for stroke [37]. Importantly, our study is the first to report that perceived discrimination is associated with self-reported stroke/TIA in diverse Hispanic/Latino adults. From a mechanistic standpoint, discrimination and emotional states such as stress and social strain result in dysregulation of the autonomic nervous system, inflammation, and an adverse cardiometabolic profile [24]. In addition, perceived discrimination has been linked to lower adherence to medical treatment and the development of unhealthy coping behaviors, such as smoking and use of illicit drugs [23,38]. While longitudinal studies establishing these links are needed, our data lay the foundation for such an investigation.

In our study, we observed that higher SDOH count is associated with an increased prevalence for all individual VRFs investigated, except for at-risk alcohol consumption. We also observed a direct relationship between SDOH count and total number of VRFs. Similar to the results obtained in REGARDS [5], where the diagnosis of stroke was ascertained by record review, we observed that the association with prevalent stroke persisted after adjustment for these VRFs and VRF count. Together, these findings highlight that VRF burden alone is not sufficient to explain the association between SDOH and self-reported stroke/TIA in Hispanic/Latino adults. Additional factors, such as allostatic load or VRF control, may contribute to this phenomenon. The modulating effect of these variables on the relationship between SDOH and risk of stroke will need to be reported in future studies. Furthermore, there are emerging initiatives in the health and non-health sectors with the goal of developing policies and procedures that address SDOH [39]. The effects of these strategies on stroke risk, however, are still unknown.

Our study has several limitations. First, several outcomes were self-reported with the consequent risk of recall bias and diagnosis inaccuracy. However, it should be noted that the prevalence of stroke/TIA of 3.3% in our study, is comparable to estimates obtained in NHANES (National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey) and the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System [40]. With data from the Study of Latinos-Investigation of NeuroCognitive Aging MRI, an ongoing ancillary study of HCHS/SOL, we will be able to investigate the association of SDOH with imaging-based cerebrovascular outcomes. Second, our study was restricted to prevalent stroke/TIA. Due to the cross-sectional nature of analyses, we cannot exclude the possibility that some of the SDOH are a consequence (as opposed to a risk) of stroke/TIA. In addition, our results cannot be directly compared to those obtained in REGARDS which investigated incident stroke. HCHS/SOL is collecting prospective information on incident stroke events, which will allow investigation of the relationship of SDOH with centrally adjudicated incident stroke and permit a more direct comparison with REGARDS. Third, there is currently no uniform definition of SDOH. In our study, we used variables included in Phenx toolkit and the Everyone project and applied core individual-level factors that have been previously linked to CVD health and outcomes [9,10]. All the variables used in this study were ascertained at Visit 2, except for discrimination which was only available at Visit 1. Therefore, we cannot exclude the possibility that this variable remained unchanged at Visit 2. However, we opted to include it in our analyses given the well-established link between socioeconomic inequalities, which more commonly affect diverse populations, and the increased risk of adverse CVD outcomes. Fourth, the HCHS/SOL uses sampling weights that are calibrated using US 2010 Census data for the population in the target geographic areas. Thus, the generalizability of our findings is limited to Hispanic/Latino individuals aged 18–74 years living in the four sampled urban communities.

It should be noted that the variables included in this study can affect health through different mechanisms and some of the relationships are not unidirectional. Individuals with low acculturation, for example, have poor work opportunities and other conditions which have a detrimental effect on the overall health [3]. At the same time, several studies in HCHS/SOL have shown that less acculturated individuals have better cardiovascular health profiles [29]. In our study, acculturation was not associated with prevalent stroke/TIA. However, we cannot exclude the possibility that aspects of the acculturative process, including health literacy, influence such association. In addition, it has been proposed that provider- (e.g., unconscious bias and lack of cultural competency), health system- (e.g., restricted access to care and inadequate quality of care), and policy-level (e.g., structural racism and resource allocation) factors also influence stroke risk and their lack of availability is a limitation of this study [2]. Also, no single parameter can fully capture social and economic conditions. Thus, it has been proposed that the use of multiple individual-level indicators of these conditions may be superior to single indicators to assess social inequities and their contribution to the development of disease [41]. This is one of the intrinsic strengths of HCHS/SOL, as it is one of the largest, most diverse, and comprehensively characterized cohorts of Hispanic/Latino adults living in the US.

Conclusions

Our results demonstrate that a higher number of unfavorable SDOH are associated with prevalent stroke/TIA and VRF burden among diverse Hispanic/Latino adults. However, VRF individually and as a count, did not completely explain the association between SDOH and self-reported stroke/TIA suggesting the contribution of non-VRF mechanisms. Our findings also suggest that among the SDOH examined, low income, lack of social support, not being employed, perceived discrimination, and chronic stress, may be particularly important for stroke/TIA in Hispanic/Latino adults. In agreement with the 2021 American Heart Association Guidelines for the Prevention of Stroke in Patients With Stroke and TIA [42], our results emphasize the importance of evaluating and addressing SDOH as a way to mitigate the burden of stroke/TIA in Hispanics/Latinos.

Supplementary materials

Supplementary materials related to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.5853/jos.2023.00626.

Overall test for significance between social determinants of health groups (continuous variable) and each vascular risk factor

Logistic regression analysis for the association between number of social determinants of health (SDOH) and prevalent vascular risk (multiple imputation data)

Weighted Percentages for the total number of vascular risk factors for each the social determinants of health (SDOH) category (multiple imputation data)

Notes

Funding statement

The Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos is a collaborative study supported by contracts from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) to the University of North Carolina (HHSN268201300001I/N01-HC-65233), University of Miami (HHSN268201300004I/N01-HC-65234), Albert Einstein College of Medicine (HHSN268201300002I/N01-HC-65235), University of Illinois at Chicago – HHSN268201300003I/N01-HC-65236 Northwestern University), and San Diego State University (HHSN268201300005I/N01-HC-65237). The following Institutes/Centers/Offices have contributed to the HCHS/SOL through a transfer of funds to the NHLBI: National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities, National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders, National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, NIH Institution-Office of Dietary Supplements. Melissa Lamar’s effort was further supported by R01 AG062711.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest.

Author contribution

Conceptualization: GT, FT, MD. Study design: GT, FT, LG, MD. Methodology: GT, FT, LG, LM. Data collection: all authors. Investigation: GT, FT, LG, ML. Statistical analysis: GT, FT, LG, JC. Writing—original draft: GT, FT. Writing—review & editing: all authors. Funding acquisition: MD. Approval of final manuscript: all authors.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the staff and participants of HCHS/SOL for their important contributions. A complete list of staff and investigators is available on the website https://sites.cscc.unc.edu/hchs/StudyOverview.