Diabetes and Stroke: What Are the Connections?

Article information

Abstract

Stroke is a major cause of death and long-term disability worldwide. Diabetes is associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular complications, including stroke. People with diabetes have a 1.5–2 times higher risk of stroke compared with people without diabetes, with risk increasing with diabetes duration. These risks may also differ according to sex, with a greater risk observed among women versus men. Several mechanisms associated with diabetes lead to stroke, including large artery atherosclerosis, cerebral small vessel disease, and cardiac embolism. Hyperglycemia confers increased risk for worse outcomes in people presenting with acute ischemic stroke, compared with people with normal glycemia. Moreover, people with diabetes may have poorer post-stroke outcomes and higher risk of stroke recurrence than those without diabetes. Appropriate management of diabetes and other vascular risk factors may improve stroke outcomes and reduce the risk for recurrent stroke. Secondary stroke prevention guidelines recommend screening for diabetes following a stroke. The diabetes medications pioglitazone and glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists have demonstrated protection against stroke in randomized controlled trials; this protective effect is believed to be independent of glycemic control. Neurologists are often involved in the management of modifiable risk factors for stroke (including hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and atrial fibrillation), but less often in the direct management of diabetes. This review provides an overview of the relationships between diabetes and stroke, including epidemiology, pathophysiology, post-stroke outcomes, and treatments for people with stroke and diabetes. This should aid neurologists in diabetes-related decision-making when treating people with acute or recurrent stroke.

Introduction

Stroke resulted in 6.55 million deaths and was ranked the second leading cause of death worldwide in 2019 [1]. In addition to high mortality, stroke is associated with a high rate of morbidity, accounting for 143 million disability-adjusted life years [1]. Modifiable risk factors for stroke include hypertension, hyperlipidemia, cigarette smoking, obesity, sedentary lifestyle, cardiac causes, including atrial fibrillation, and diabetes [2]; prevention of stroke requires comprehensive management of these risk factors.

Diabetes is a highly prevalent, chronic disease [3], and a well-established risk factor for stroke [4]. It often coexists with other cardiometabolic risk factors that independently increase the risk of stroke [4]. In people with diabetes, the risk of stroke is increased approximately two-fold compared with people without diabetes, when adjusted for age [5]. In addition, patients with diabetes have worse post-stroke outcomes and a greater risk for stroke recurrence as compared with those without diabetes [6-11].

No major clinical trials have evaluated specific stroke prevention strategies in individuals with diabetes, and stroke prevention remains a significant unmet need in the clinical management of these patients [12]. As the incidence of diabetes is increasing rapidly [3], leading to a higher overall stroke burden, neurologists should be equipped not only with knowledge of how diabetes impacts the risk of first and recurrent strokes, but also of the different strategies to prevent stroke in people with diabetes. This review article provides an overview of the connection between diabetes and stroke, including epidemiology, pathophysiology, post-stroke outcomes, and the impact of glucose-lowering agents on stroke risk; this will aid neurologists in treating individuals with diabetes and stroke.

Diabetes as a risk factor for stroke

According to the International Diabetes Federation, approximately 537 million adults (20–79 years) are living with diabetes; this is expected to rise to 643 million by 2030 and 783 million by 2045 [3]. Diabetes can lead to various microvascular and macrovascular complications, including stroke. In 2019, there were 12.2 million incident cases of stroke and 101 million prevalent cases of stroke worldwide [1]. These incidence and prevalence figures have increased substantially since 1990 [1]. Furthermore, point estimates of incident and prevalent strokes are higher among women than men (6.44 million and 56.4 million for women, respectively, vs. 5.79 million and 45.0 million for men, respectively) [1].

The prevalence of diabetes in people with all types of stroke is 28% [13]. The rate is greater in those with ischemic (33%) compared with hemorrhagic (26%) stroke [13]. Among people with ischemic stroke, those with diabetes are relatively younger and have more comorbidities than those without diabetes [10]. Moreover, the likelihood of stroke recurrence is greater for individuals with diabetes than those without diabetes [8]. A meta-analysis demonstrated a significantly higher risk of stroke recurrence in individuals with previous ischemic stroke with diabetes than in those without diabetes (hazard ratio [HR]: 1.50; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.36–1.65) [8].

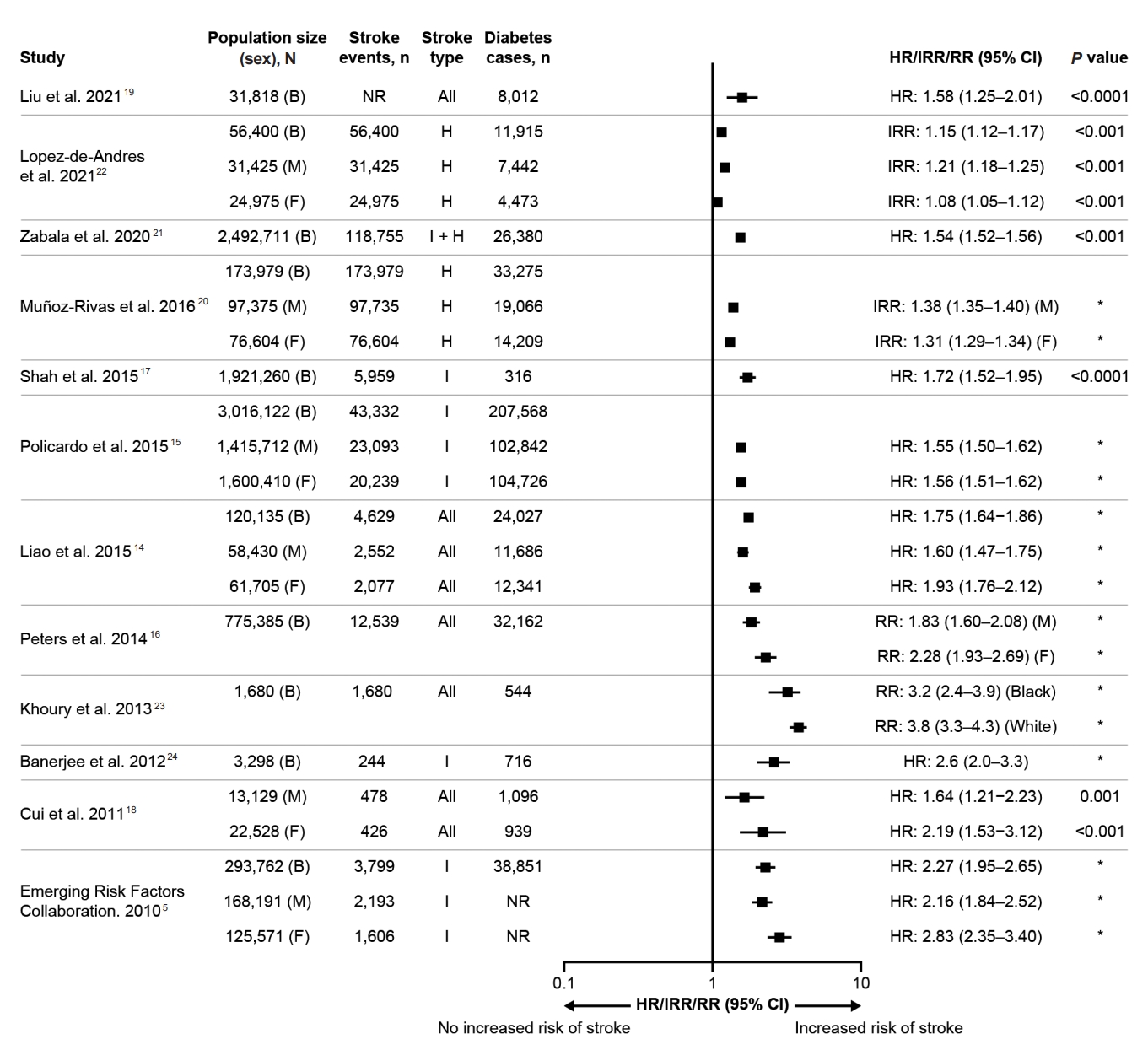

To assess the risk of stroke associated with diabetes, a search of MEDLINE (via PubMed) was performed using the terms ‘stroke’ (title) AND ‘diabetes’ (title) AND ‘risk’ (text word), retrieving only citations limited to English language, human studies, and publication dates between 2010 and 2022 (n=223). Search results were screened based on titles and abstracts, and only those that reported risks of stroke in patients with diabetes compared with those without diabetes (sample size >1,000) were included. A summary of the risk of stroke in people with diabetes compared with those without diabetes is shown in Figure 1. These epidemiologic studies demonstrated that diabetes is an independent risk factor for stroke [5,14-24]. Furthermore, the risk of stroke is higher in people with either type 1 diabetes (T1D) (HR: 1.50; 95% CI: 1.23–1.83) or type 2 diabetes (T2D; HR: 1.76; 95% CI: 1.65–1.87) compared with people without diabetes [14].

Risk of stroke in people with diabetes compared with those without diabetes (studies between 2010 and 2022 with N>1,000). B, both; CI, confidence interval; F, females; H, hemorrhagic; HR, hazard ratio; I, ischemic; IRR, incidence risk ratio; M, males; NR, not reported; RR, relative risk. *No P value available.

There are also differences in risk according to the stroke type. The adjusted HRs are 2.27 (95% CI: 1.95–2.65) for ischemic stroke and 1.56 (95% CI: 1.19–2.05) for hemorrhagic stroke in people with diabetes versus those without diabetes [5]. Furthermore, there appear to be differences in the risk of stroke between sexes among people with diabetes, with evidence suggesting a greater risk amongst women than men [5,14,16,18]. In a meta-analysis, the adjusted relative risk of any stroke associated with diabetes was 2.28 (95% CI: 1.93–2.69) in women, whereas it was 1.83 (95% CI: 1.60–2.08) in men, when compared with individuals without diabetes [16]. However, other studies have reported contradictory findings regarding sex differences in the risk of stroke associated with diabetes when analyzing specific age groups or stroke types (Figure 1) [15,17,22].

In addition to diabetes, prediabetes—defined by the American Diabetes Association (ADA) as impaired fasting glucose (fasting plasma glucose 100–125 mg/dL [5.6–6.9 mmol/L]) and/or impaired glucose tolerance (plasma glucose levels 2 hours after 75 g of oral glucose intake of 140–199 mg/dL [7.8–11.0 mmol/L]) and/or glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) 5.7%–6.4% (39–47 mmol/L) [25]—may be associated with a modestly higher risk of future stroke compared with those with normal glycemia [26].

Moreover, the duration of diabetes is independently associated with the risk of ischemic stroke; the risk has been reported to increase by 3% each year and triples in those who have had diabetes for ≥10 years, compared with those without diabetes [24]. Several explanations may account for the association between diabetes duration and stroke, including an increased risk of atherosclerotic lesions [24,27,28] and more severe endothelial dysfunction with an increased duration of diabetes [29]. Obesity, a common comorbidity in people with diabetes, may also contribute to the development of endothelial dysfunction as a result of its metabolic impacts, including a disruption to the balance between vasoconstrictors and vasodilators, growth-promoting and inhibitory factors, proatherogenic and antiatherogenic factors, and procoagulant and anticoagulant factors [27]. In addition, hypertension is common in people with diabetes and is often coexistent with other factors, including microvascular disease, metabolic derangements, vascular fibrosis, and autonomic dysfunction, which contribute to congestive heart failure and increase the risk of stroke [27,28]. Despite the association between longer diabetes duration and increased risk of stroke, diabetes-related complications (including stroke) may be present even at the time of diabetes diagnosis [3].

Pathophysiologic relationship between diabetes and stroke

Ischemic stroke can result from three main common causes, including large artery atherosclerosis, cerebral small vessel disease (SVD), and cardiac embolism (Figure 2), as well as a number of less common causes. Diabetes may play an active role in each of the three major mechanisms [30-32].

Large artery atherosclerosis

Atherosclerosis of cervical and intracranial arteries is one of the leading causes of ischemic stroke [31] and results in artery-to-artery embolism and impaired distal perfusion [33]. Both T1D and T2D are understood to be independent risk factors for accelerated atherosclerosis development [34]. Dyslipidemia, hyperglycemia, and insulin resistance result in a spectrum of physiological changes, including the formation of atherogenic low-density lipoprotein (LDL), advanced glycation end products, and activation of pro-inflammatory signaling that impact the arterial wall, leading to atherosclerotic lesion development [34]. Inflammation also plays a key role in the development of atherosclerotic plaque, and an increased inflammatory response is frequently observed in individuals with diabetes [28], demonstrated by elevated levels of C-reactive protein (CRP) [35], a sensitive marker of systemic inflammation.

Cerebral SVD

Cerebral microvascular dysfunction is apparent in both people with diabetes and those with prediabetes, suggesting the processes behind cerebral SVD start prior to the onset of diabetes [36]. Impaired cerebral microvasculature predisposes an individual to lacunar and hemorrhagic strokes [36], and it is estimated that cerebral SVD accounts for around 25% of all ischemic strokes (irrespective of diabetes diagnoses) [32]. Hyperglycemia, obesity, insulin resistance, and hypertension are believed to be the main drivers of diabetes-related cerebral microvascular dysfunction [36]. Furthermore, increased arterial stiffness, a common occurrence in diabetes, exposes the small vessels in the brain to abnormal flow pulsations, which may also contribute to the pathogenesis of cerebral SVD [28]. Arterial stiffness in diabetes may result from pathological changes in the vascular bed, such as reduced nitric oxide bioavailability, increased oxidative stress, chronic low-grade inflammation, increased sympathetic tone, and changes in type or structure of elastin and/or collagen in the arterial wall [28,37]. Increased oxidative stress and inflammation are closely linked and are both believed to contribute to microvascular endothelial dysfunction, which has also been proposed as the initial ‘driver’ of SVD [36]. Microalbuminuria is a complication of diabetes and is associated with markers of microvascular endothelial dysfunction, including vascular endothelial growth factor, intracellular adhesion molecule-1, and vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 [36].

Cardiac embolism

Atrial fibrillation is a well-established cause of cardioembolic stroke [30]. The current model for the mechanisms of stroke in atrial fibrillation is complex and thought to be a composite process of atrial remodeling (atrial cardiomyopathy), of which atrial fibrillation is a manifestation, resulting in an increased risk of cardioembolic stroke [38]. Individuals with T2D have an overall 35% higher risk of atrial fibrillation compared with the general population [39]. The exact mechanisms by which diabetes increases the risk of atrial fibrillation require further investigation, but it is thought that increased levels of reactive oxygen species and/or advanced glycation end products in diabetes trigger electrical, structural, and autonomic remodeling in the atria [40].

Hyperglycemia as a predictor of poor outcomes in stroke

Elevated blood glucose is a common occurrence in the early stages of stroke [41]. The prevalence of hyperglycemia, defined as blood glucose level >6.0 mmol/L (108 mg/dL), has been reported in up to two-thirds of all ischemic stroke subtypes upon hospital admission [41]. It is important to highlight that the relationship between stroke outcomes and hyperglycemia is bidirectional: whilst high blood glucose may contribute to poor stroke outcomes, severe ischemic stroke may also be the cause of post-stroke hyperglycemia [41]. Two main mechanisms seem to underlie the occurrence of acute hyperglycemia following ischemic stroke: a generalized stress reaction that involves stimulation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis, leading to raised levels of glucocorticoids and activation of the sympathetic autonomic nervous system, and an increased immune response resulting in insulin resistance post-stroke [42]. This theory is further supported by the observation that increased stroke severity is generally associated with an increased degree of hyperglycemia [42].

There is evidence to suggest that acute hyperglycemia at the time of ischemic stroke may be associated with poor outcomes [41]. Compared with people with normal glycemia, the unadjusted relative risk of in-hospital or 30-day mortality after an ischemic stroke in individuals who have hyperglycemia at admission is 3.28 (95% CI: 2.32–4.64) for those without known diabetes and 2.00 (95% CI: 0.04–90.08) for those with a known history of diabetes [43]. The association between hyperglycemia and poor clinical outcomes is even more pronounced when hyperglycemia persists during the first few days after acute ischemic stroke onset [44]. Despite this, strict glucose control at the time of acute ischemic stroke has not been shown to improve clinical outcomes [45].

The relationship between acute hyperglycemia following a stroke and poor outcomes is independent from other predictors of poor clinical outcome, such as age, stroke severity, or infarct volume [46]. Aggravated cerebral damage through impaired recanalization, decreased reperfusion, increased reperfusion injury, and possibly direct tissue injury may account for the association between hyperglycemia and worse post-stroke outcomes [41].

Post-stroke outcomes in people with diabetes

To assess the relationship between diabetes and stroke outcomes, a similar search of MEDLINE as described above was performed using the terms ‘stroke’ (title) AND ‘diabetes’ (title) AND ‘outcome’ (text word) (n=672). Search results were screened based on titles and abstracts, including only those that reported outcomes of stroke in patients with diabetes compared with those without diabetes, with a sample size >1,000. Fourteen studies fulfilled these criteria and 658 were excluded. A summary of post-stroke outcomes in people with and without diabetes reported in the identified literature is summarized in Table 1.

Most, though not all, studies have shown that people with stroke and diabetes have worse post-stroke outcomes compared with those with stroke but without diabetes [6-11,47-49]. Postdischarge mortality rates are higher in individuals with ischemic stroke and diabetes versus those without diabetes [6,10,47,48]. In addition, median survival is lower in people with either type of stroke (i.e., ischemic or hemorrhagic) and diabetes compared with those without diabetes [7]. Stroke severity alone is unlikely to explain the higher mortality and lower survival in people with diabetes [13]. In general, the length of in-hospital stay is longer among individuals with stroke who have diabetes compared with those without diabetes [6]. Furthermore, a meta-analysis exploring the effect of diabetes on stroke recurrence among individuals with ischemic stroke showed that the risk of stroke recurrence was significantly higher in those with diabetes versus those without diabetes (HR: 1.50; 95% CI: 1.36–1.65) [8]. However, it is noteworthy that there is no association between HbA1c level over time and risk of stroke recurrence [50].

There is also evidence that diabetes is associated with poorer cognitive performance after stroke compared with those without diabetes. Post-stroke cognitive impairment occurs frequently, with 25%–30% of ischemic stroke survivors developing immediate or delayed vascular cognitive impairment or vascular dementia [51]. Moreover, it has been shown that people with T2D have poorer cognitive performance 3–6 months after an ischemic stroke versus those without T2D [9]. While the mechanism of the interaction between stroke and diabetes on cognition is not clear, it has been suggested that the proinflammatory processes associated with diabetes may exacerbate ischemic damage in the brain [52]. Diabetes may also contribute to the underlying vascular and neurodegenerative pathology that leads to cognitive decline [36]. Controlling vascular disease risk factors, including diabetes, is therefore considered essential to reduce the burden of cognitive dysfunction after stroke.

Prevention of stroke in people with diabetes or prediabetes

Stroke prevention requires management of modifiable risk factors through lifestyle changes and pharmacological or surgical interventions [12]. Intensive multiple risk factor intervention has been shown to significantly reduce the occurrence of first stroke as well as the number of recurrent cerebrovascular events among people with T2D [53]. In a recently reported Danish cohort study of patients with T2D and no prior atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD), the 5-year risk of first-time ischemic stroke was approximately halved in the period from 1996 to 2015 [54]. This reduction in risk coincided with a marked increase in the use of prophylactic cardiovascular medications, including statins and antihypertensive drugs [54]. Neurologists who care for people who have had a stroke are typically involved in the treatment of atrial fibrillation, carotid stenosis, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia, but not as often in the management of diabetes. Therefore, raising awareness of diabetes management among neurologists may be beneficial, particularly in the context of recent evidence to support stroke reduction with certain glucose-lowering agents [55,56].

There is a presumed benefit in identifying all individuals with diabetes after an ischemic stroke so that they can be offered appropriate treatment. If a person has a known history of diabetes and is already taking glucose-lowering agents at the time of the stroke, it is important to assess whether diabetes management can be further optimized. In people who do not have a known history of diabetes, the American Heart Association (AHA)/American Stroke Association (ASA) secondary stroke prevention guideline recommends screening for prediabetes/diabetes with HbA1c levels and an oral glucose tolerance test or fasting blood glucose test after the ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack (TIA) [12]. Although acute and chronic hyperglycemia has been associated with increased incidence and morbidity of stroke, intensive lowering of glucose levels has not been shown to prevent macrovascular events, such as stroke [12]. However, a multifactorial approach to manage glucose, blood pressure, and lipids, along with the use of renin-angiotensin system inhibitors, statins, and aspirin (where appropriate), has been shown to reduce both microvascular and cardiovascular complications of diabetes [57]. After a follow-up period of 21 years, this multifactorial approach was also shown to reduce the risk of incident and recurrent stroke [53]. In addition to the multifactorial approach, other evidence has emerged indicating that specific glucose-lowering agents (glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists [GLP-1 RAs] and pioglitazone) can reduce stroke risk [55,56].

Evidence for reduced risk of stroke with certain medications for diabetes

A large number of classes of non-insulin glucose-lowering agents are available to treat diabetes, including GLP-1 RAs, thiazolidinediones, sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors (SGLT-2is), dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors (DPP-4is), sulfonylureas, biguanides, meglitinides, and alpha-glucosidase inhibitors. Some of these agents have been studied in cardiovascular outcome trials (CVOTs) to determine their safety and, in some cases, demonstrated superiority compared with placebo. A number of agents from the SGLT-2i and GLP-1 RA classes have been shown to reduce the risk of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) in large well-designed trials [56,58] and, as such, are recommended prominently in both diabetes and cardiovascular international guidelines [4,12,59,60]. Thiazolidinediones, an insulin-sensitizing drug class, have demonstrated neutrality for MACE but may have benefits in stroke prevention [61]. In contrast, DPP-4is do not seem to have any beneficial effect on cardiovascular outcomes [62]. Other glucose-lowering agents available to treat people with diabetes include sulfonylureas, metformin, meglitinides, and α-glucosidase inhibitors; evidence for the effect of these agents on cardiovascular outcomes is limited and conflicting. Furthermore, therapy with basal insulin has shown a neutral effect on cardiovascular outcomes, including stroke [63].

Evidence of a cardiovascular benefit from these large CVOTs suggests that some glucose-lowering agents may reduce the incidence of stroke, a component of the composite primary outcome in these trials.

Combined primary and secondary prevention of stroke

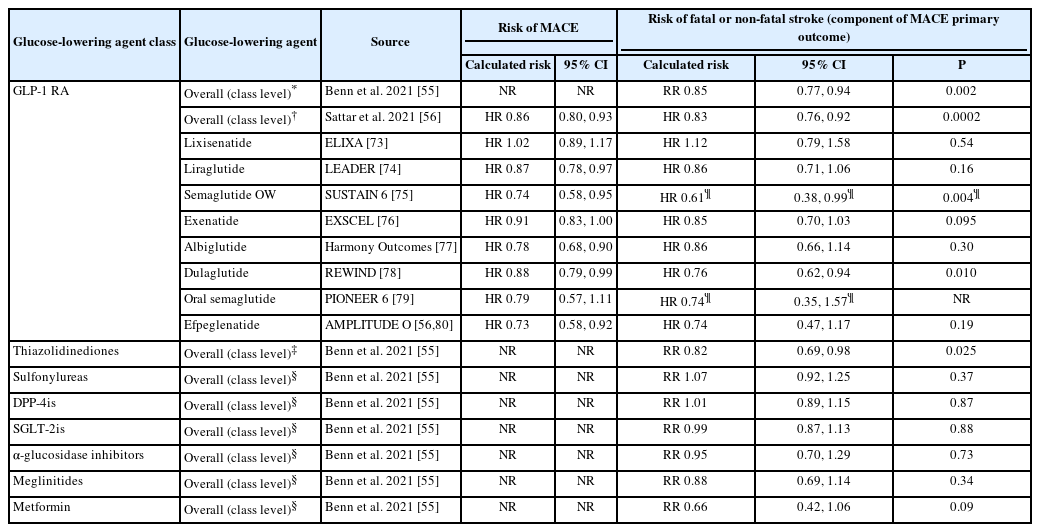

Meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials of >12 months’ duration involving glucose-lowering agents have demonstrated that the majority of such therapies had no known effect on the risk of stroke, with the exception of thiazolidinediones and GLP-1 RAs (Figure 3 and Table 2) [55]. In these meta-analyses, the risk ratio for stroke was 0.85 (95% CI: 0.77–0.94; P=0.002) for GLP-1 RAs and 0.82 (95% CI: 0.69–0.98; P=0.025) for thiazolidinediones, whilst other glucose-lowering agents (mentioned above) individually did not show statistical evidence of an effect on stroke risk (Figure 3 and Table 2) [55]. It should be noted that, among the five studies investigating thiazolidinediones that are included in the meta-analysis, all investigated pioglitazone except for one, which investigated rosiglitazone. The risk of stroke in this individual study was found to be increased with rosiglitazone compared with control treatment (relative risk: 1.40; 95% CI: 0.45–4.40) [55].

Therapies available for treatment of people with diabetes according to their effect on reduction of stroke risk [55, 65-67]. Data shown for each drug class are for overall risk of stroke relative to placebo, from Benn et al [55]. CI, confidence interval; DPP-4is, dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors; GLP-1 RA, glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist; SGLT-2is, sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors; RR, relative risk. *Glucose-lowering agent has shown evidence of improvement in stroke risk when analyzed at individual level within drug class, within meta-analyses or post hoc studies mainly utilizing data from cardiovascular outcome trials in which stroke formed part of the primary outcome; †Lacks statistical evidence of an effect on stroke risk.

Risk of fatal or non-fatal stroke associated with the use of glucose-lowering drugs in people with diabetes

Meta-analyses of the large CVOTs of GLP-1 RAs in people with T2D demonstrated a 15%–17% statistically significant reduction in risk of fatal or non-fatal stroke with GLP-1 RAs compared with placebo (Table 2), with no major differences in stroke outcomes between the trials [56].

Secondary prevention of stroke

Pioglitazone has been investigated for secondary stroke prevention in the Insulin Resistance Intervention after Stroke (IRIS) trial, which showed that, among people who had experienced a recent ischemic stroke or TIA and had insulin resistance, but not diabetes, the risk of fatal or non-fatal stroke or myocardial infarction (MI) was lower among those who received pioglitazone compared with those who received placebo (HR: 0.76; 95% CI: 0.62–0.93; P=0.007) [61]. The PROactive (PROspective pioglitAzone Clinical Trial In macroVascular Events) trial also investigated the effect of pioglitazone on macrovascular outcomes in people with T2D and found a non-significant stroke risk reduction [64]; however, in a post hoc analysis of patients with prior stroke, pioglitazone significantly reduced the risk of recurrent stroke [65].

To date, no clinical trial has studied the use of SGLT-2is or GLP-1 RAs for the secondary prevention of stroke in patients with diabetes as a primary outcome. Post hoc analyses of the LEADER (Liraglutide Effect and Action in Diabetes: Evaluation of Cardiovascular Outcome Results) and SUSTAIN 6 (Semaglutide Unabated Sustainability in Treatment of Type 2 Diabete) trials with liraglutide and semaglutide, respectively, evaluated the treatment effect in subgroups of people with history of stroke or MI, and found no significant decreases in the risk of non-fatal stroke compared with placebo [66,67]. However, these subgroup analyses were underpowered, and randomized trials specifically dedicated to testing the effect of these glucose-lowering agents on secondary stroke prevention should be conducted.

GLP-1 RAs and pioglitazone and their mechanisms of cardiovascular benefit

GLP-1 RAs have multisystem effects that result in improved pancreatic response to food, delayed gastric emptying and increased satiety, shown to reduce blood glucose levels, body weight, and blood pressure [68]. In addition to these effects, the large CVOTs have shown that most GLP-1 RAs reduce cardiovascular event risk among those with T2D who are at high cardiovascular risk or with previous ASCVD [56].

Several possibilities could account for the beneficial effects of GLP-1 RAs on cardiovascular outcomes. These include, but are not limited to, a reduction in HbA1c, LDL cholesterol, blood pressure, weight, urine albumin/creatinine ratio, and high-sensitivity CRP [68,69]. Intensive glycemic control achieved with agents other than GLP-1 RAs or pioglitazone has not been shown to have any significant effect on stroke events in people with T2D [55]. This suggests that the beneficial effect of GLP-1 RAs on stroke is not solely due to glycemic control.

In addition to its glycemic effects, pioglitazone exerts potential beneficial effects on inflammation, fat distribution, lipid and protein metabolism, and vascular endothelial function [61]. As noted above, pioglitazone was shown to lower the risk of combined stroke or MI, compared with placebo, in the IRIS trial [61]. How this agent decreases vascular events is unknown; however, the benefits cannot be solely explained by a thiazolidine class effect as rosiglitazone has been associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular events compared with placebo [55].

Clinical recommendations for stroke prevention

As noted, the glucose-lowering agents SGLT-2is and GLP-1 RAs are recommended in international clinical practice guidelines for diabetes and cardiovascular disease [4,59,60]. The 2022 ADA guidelines recommend a GLP-1 RA or SGLT-2i with demonstrated cardiovascular benefit in people with T2D and established ASCVD or multiple risk factors for ASCVD to reduce the risk of MACE, irrespective of glucose control and of metformin use [60]. The 2021 European Society of Cardiology Guidelines recommend the use of a GLP-1 RA or SGLT-2i with proven outcome benefits in individuals with T2D and ASCVD to reduce cardiovascular and/or cardiorenal outcomes [4]. Moreover, the 2021 AHA/ASA secondary stroke prevention guidelines recommend that, in people with an ischemic stroke or TIA who also have diabetes, treatment of diabetes should include glucose-lowering agents with proven cardiovascular benefit (thiazolidinediones, GLP-1 RAs, and SGLT-2is) to decrease the risk of future MACE, including stroke [12]. Unlike the data for pioglitazone and some GLP-1 RAs, the CVOTs of SGLT-2is do not indicate a specific effect on stroke, though some have shown a modest reduction in MACE and significant reductions in cardiovascular mortality and hospitalization for heart failure [70]. Furthermore, an expert multidisciplinary panel has developed a practical decision-making algorithm to assist in using GLP-1 RAs as part of a stroke reduction strategy as a recommended call to action for neurologists [71].

Conclusions

Epidemiologic studies have shown that diabetes is a well-established risk factor for stroke. There are several pathophysiological mechanisms wherein diabetes leads to ischemic stroke, including large artery atherosclerosis, cerebral SVD, and cardiac embolism. Not only is the presence of diabetes associated with an increased risk of stroke, but also post-stroke outcomes are generally worse in people with diabetes than in those without diabetes. While hyperglycemia at the time of stroke is also a predictor of poorer post-stroke outcomes compared with normoglycemia, intensive glucose lowering during the acute phase post-stroke does not improve stroke outcomes. Comprehensive management of all modifiable vascular risk factors is necessary to reduce the incidence and recurrence of stroke, and an individualized care strategy should be tailored to consider the patient’s comorbidities. Chronic control of hyperglycemia per se is not associated with a reduction in stroke risk. Therefore, management of diabetes in people with stroke requires more than just glucose control. Several glucose-lowering agents, including some GLP-1 RAs and pioglitazone, may have advantages in stroke prevention, as demonstrated by their cardiovascular benefits independent of glycemic control. Neurologists should familiarize themselves with the benefits of glucose-lowering agents to allow their appropriate inclusion in prevention strategies for stroke in patients with diabetes.

Notes

Disclosure

OM: Advisory Board: Novo Nordisk, Eli Lilly, Sanofi, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Boehringer Ingelheim, AstraZeneca, and BOL Pharma; research grant support through Hadassah Medical Center: Novo Nordisk and AstraZeneca; Speakers bureau: Novo Nordisk, AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly, Sanofi, Merck Sharp & Dohme and Boehringer Ingelheim.

AYYC: Honoraria for speaking or consulting from Abbott, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Bausch, Boehringer Ingelheim, Dexcom, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Insulet, Medtronic, Merck, Novo Nordisk, Sanofi, HLS Therapeutics and Takeda; participation in clinical trials supported by Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, Sanofi and Applied Therapeutics.

AAR: Advisory board member for AstraZeneca and Novo Nordisk; adverse event adjudication for trials funded by Boston Scientific and Boehringer Ingelheim; grant from Chiesi for an investigator-initiated project.

SS: Personal fees from Abbott, Allergan, AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly, Lundbeck, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, and Teva as speaker or advisor; fees from Medscape, Neurodiem Ology Medical Education for CME/education; research grants from Allergan, Novartis and Lusofarmaco; non-financial support from Abbott, Allergan, Bayer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Daiichi-Sankyo, Eli Lilly, Lundbeck, Medtronic, Novartis, Pfizer, Starmed and Teva; co-chair guideline board for European Stroke Organization; board member of the European Headache Federation; specialty chief editor in Headache and Neurogenic Pain for Frontiers in Neurology journals; associate editor for The Journal of Headache and Pain; assistant editor for Stroke journal.

Acknowledgements

Medical writing and editorial support, under the guidance of the authors, were provided by Beth Campbell, BSc, Alice Garrett, BSc MSc, and Izabel James, MBBS, from Ashfield MedComms, an Inizio company, funded by Novo Nordisk A/S.

Novo Nordisk funded the medical writing support for this review and also had a role in the review of the manuscript for scientific accuracy.

All authors contributed to the content of the review article, providing details of references that should be cited, content (and its organization) that should be included, critically reviewing each draft and approving the final draft for submission.