Epidemiological Factors of Stroke: A Survey of the Current Status in China

Article information

Abstract

Stroke is the leading cause of death in China and confers a huge burden and effort on patients and health professionals. China has the world's largest population and has been experiencing a rapid economic development. In this article, we review the current status of stroke epidemiological features and risk factors, and the recently ongoing stroke epidemiological survey in China. Epidemiological studies suggested that stroke incidence increases with age and that the elderly population is expected to increase over time in China. Stroke mortality increased gradually from 1990 to 2000 but declined since the beginning of the 21st century, probably related to better control of vascular risk factors and the advances in acute stroke care. The Chinese lifestyle has changed rapidly during the past 3 decades. Moreover, China is a big country with substantial geographic disparities. The geographical variation and chronological trend of vascular risk factors may determine changes in the prevalence and subtypes of stroke in China. In this review, the current Chinese researches on the critical management of stroke and the potential direction and support of the Chinese government are discussed.

Introduction

Stroke remains to be one of the most devastating neurological diseases. Globally, stroke is the second leading cause of death in persons older than 60 years and the fifth leading cause of death in persons aged 15 to 59 years.1 More than two thirds of stroke deaths worldwide occur are in developing countries. Among the developing countries, China has the largest population with 1.4 billion people. Stroke now has been the leading cause of death in China.2 Stroke carries an enormous financial burden, not only for the families of patients but also for society as a whole in China.3,4 In the past 30 years, China has experienced a rapid economic development. Over time, life expectancies will lengthen, the proportion of elderly people in the population will increase, and the influence of a Westernized lifestyle might shift disease patterns, which may consequently result to an increase in the number of stroke patients. Stroke epidemiological features can help us identify groups of individuals or regions at higher risk of stroke and therefore push the direction of stroke prevention. In this article, we review the current status of the epidemiological features and risk factors of stroke, a recently ongoing stroke epidemiological survey, and the future direction of stroke management in China.

Incidence

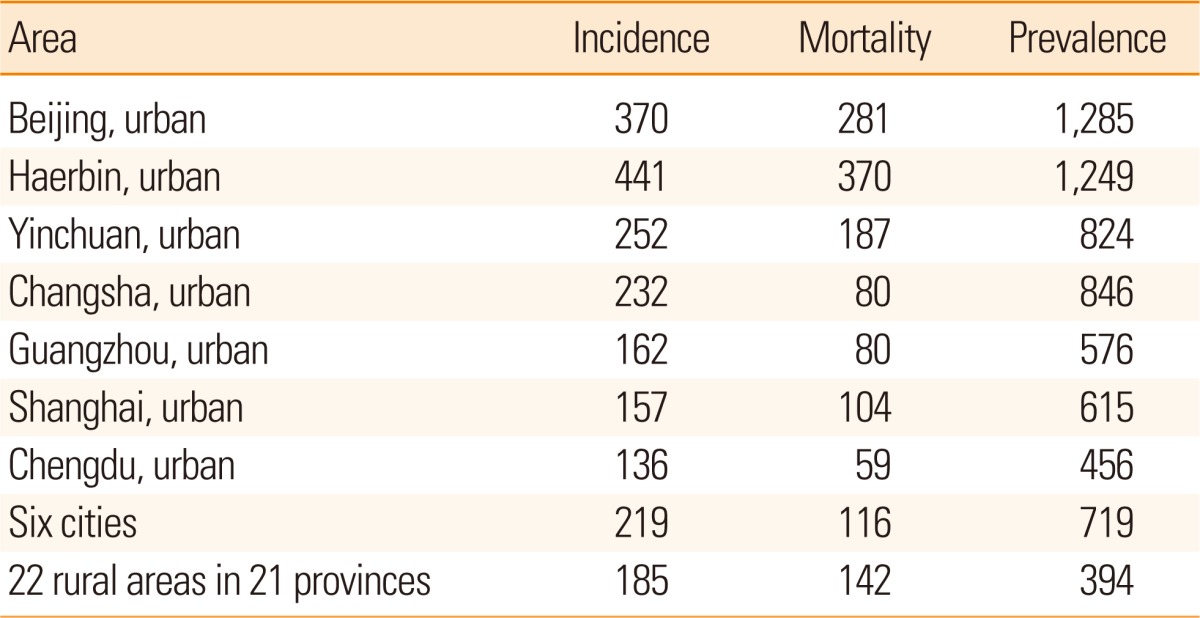

The stroke incidence remains relatively diverse worldwide. Three earlier studies used a similar research design, using a retrospective door-to-door survey, to investigate the stroke incidence in various populations in China since the 1980s.5-7 The total mean age-adjusted incidence of first-ever stroke ranged from 116 to 219 cases per 100,000 population per year (using the 1960 total US population to adjust age). The first multicenter and community-based study on stroke incidence was the 6-city incidence study,5 which was completed in 1983. A sample population of 63,195 was selected from 6 cities, in which a stroke incidence of 219 cases per 100,000 population per year was reported (Table 1).8 The second survey was accomplished in 1985. The scope of the investigation covered 22 rural areas in 21 provinces and a sample population of 246,812. The survey indicated a stroke incidence of 185 cases per 100,000 population per year (Table 1).6 The lowest mean incidence of total stroke was 115.61 cases per 100,000 population per year, which was reported in 1987 by the largest retrospective epidemiological study7 and substantially lower than the stroke incidence reported by the 2 aforementioned studies. The survey included a 5,800,000 population from 29 provinces or cities. The reason for the difference in the reported incidence is unclear but probably related to the difficulties involved in managing and ensuring good-quality data obtained from a huge sample population.

For incidence studies, a prospective design is clearly more ideal than a retrospective one. In China, several multicenter and prospective studies have been designed using the same criteria since the 1980s.9-11 The World Health Organization's Monitoring of Trends and Determinants of Cardiovascular Disease project (1985-1990) is the only source of standard data for comparison in different populations of many countries. Beijing was the only Asian area included in the study. The age-adjusted stroke attack incidence rate in Beijing was 175 cases in women and 247 cases in men per 100,000 population per year, the second and sixth highest rates, respectively, in the World Health Organization's Monitoring of Trends and Determinants of Cardiovascular Disease data.9 Another 2 prospective studies indicated that the stroke incidence in their respective monitoring groups varied from 165.4 to 212.2 cases in women and from 182.1 to 314 cases in men per 100,000 population per year.10,11 These 2 studies were well designed and implemented using standard diagnostic criteria, hence their relatively reliable findings (Table 2). All previous Chinese epidemiological studies suggested that the stroke incidence rate increases with age. The highest rates were reported in people older than 75 years, which were 30 times higher than those reported in the age group 35-44 years.12

Prevalence

Prevalence is related to incidence and mortality. High incidence and low mortality can result in high prevalence. Globally, an estimated 16 million people experience a first-ever stroke in the year 2005, with an estimated prevalence of 62 million stroke survivors.13 As a disease of aging, the prevalence of stroke is expected to increase significantly around the world in the years ahead as the global population older than 65 years continues to increase by approximately 9 million people per year.14 Three studies investigated the stroke prevalence in China. As shown in Table 1, the age-adjusted stroke prevalence in 6 cities was 719 cases per 100,000 population for all ages and that in 22 rural areas in 21 provinces was 394 cases per 100,000 population for all ages.5,6 Another retrospective epidemiological study7 of 29 provinces reported that the lowest age-adjusted stroke prevalence rate was 259.86 cases per 100,000 population, substantially lower than those in the 2 aforementioned studies (Table 1). Geographical variations of 1,249-1,285 and 95 cases per 100,000 population were respectively observed in northern cities such as Harbin and Beijing and southern rural areas in the Guangxi province.12 The prevalence of stroke is higher in urban areas than in rural areas (295.30-377.63 vs. 193.56 cases per 100,000 population).7

Mortality

The World Health Organization's Monitoring of Trends and Determinants of Cardiovascular Disease project indicated that the stroke mortality in Beijing in the 1980s was 58 deaths in women and 66 deaths in men per 100,000 population per year, the second and fifth highest, respectively, in 17 populations.9 Recently, stroke has exceeded heart disease to become the leading cause of death, according to the third survey in China for the period 2004-2005. The stroke mortality recorded was 124.15 deaths in women and 148.57 deaths in men per 100,000 population per year.2 The China Health Statistical Yearbooks8 reveal the trends of stroke mortality in China (Figure 1). Stroke mortality in the urban and rural areas increased gradually from 1990 to 2000 and then began decreasing since the beginning of the 21st century. Some developed countries such as the United States, Canada, France, Switzerland, and Australia have experienced declines in mortality, which may be associated with the increased use of preventative treatment, better control of vascular risk factors, and the advances in acute stroke care. However, the stroke mortality is on a rebound after 2006 (Figure 1). Another notable phenomenon is that the stroke mortality was higher in the urban areas than in the rural areas during the period 1988-2006, whereas an opposite trend was observed after 2006. The reasons for the rebound in mortality and reversal of the trend in the urban and rural areas remain unclear.

Stroke types and subtypes

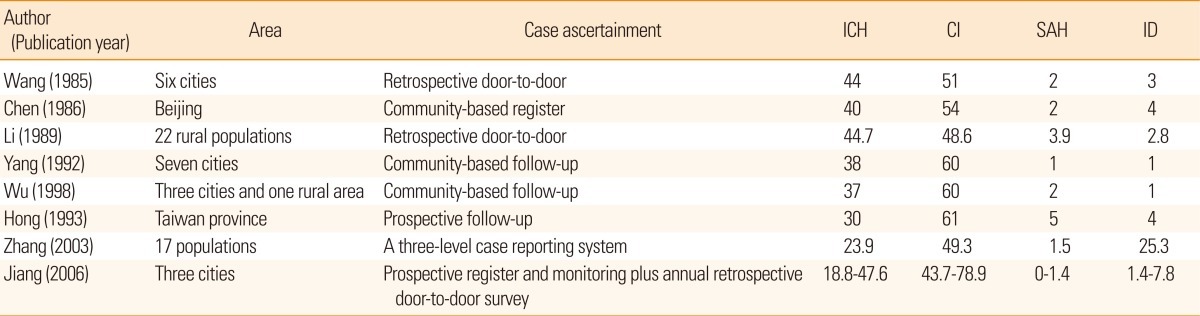

In some developed countries, up to 67.3-80.5% of stroke cases are attributed to ischemic stroke, whereas only 6.5-19.6% are attributed to intracerebral hemorrhage; approximately 0.8-7.0%, to subarachnoid hemorrhage; and 2.0-4.5%, to undetermined types.15 The Greater Cincinnati/Northern Kentucky Stroke Study and National Institutes of Neurological Disorders and Stroke suggested higher proportions of ischemic stroke cases. Of all stroke cases, 87% were ischemic, 10% were intracerebral hemorrhage, and 3% were subarachnoid hemorrhage.16 Most of the Chinese studies have suggested that the proportion of intracerebral hemorrhage cases is significantly higher in China than in Western countries. Some studies in China reported the proportion of each stroke type (Table 3).8 As shown in Table 3, earlier studies (before 1990) reported that cerebral infarction accounted for 48.6-51.0% of the total number of stroke cases; intracerebral hemorrhage, for 44.0-44.7%; subarachnoid hemorrhage, for 2.0-3.9%; and undetermined types, for 2.8-3.0%.5 In these studies, only a few patients underwent computed tomography (CT); thus, their results might be unreliable. However, the 2 studies in 1992 and 1998 evaluated patients who all underwent CT scan, reporting almost identical proportions of intracerebral hemorrhage (37% vs. 38%), which were 3 times higher than that reported for Western populations. In recent studies,11,17 more than three quarters of patients (75.3-98.0%) underwent CT scan, hence the relatively reliable results. Jiang et al.11 reported that the proportion of each stroke type ranged from 43.7% to 78.9% for ischemic stroke and from 18.8% to 49.0% for hemorrhagic stroke. Another study observed that intracerebral hemorrhage is the most prevalent (55.4% of all stroke cases) in Changsha, a city in South Central China.18 The reasons for the higher incidence of intracerebral hemorrhage in China are unclear, but the high prevalence of hypertension may be the most plausible explanation.

A review of published studies and data from clinical trials found that hospital admissions for intracerebral hemorrhage have increased by 18% worldwide in the past 10 years, probably because of the increase in the number of elderly people, poor blood pressure control, and the increasing use of anticoagulants, thrombolytics, and antiplatelet agents.19 On the contrary, the China Acute Cerebrovascular Events Registers reported that ischemic stroke cases were increasing and intracerebral hemorrhage cases in China were decreasing.20 In the last 2 decades, the incidence of hemorrhagic and ischemic strokes declined by 1.7% and increased by 8.7% annually, respectively. The decrease in hemorrhagic stroke should be closely related with the improvements in health care that came with the economic development, but the improvement in hypertension control is the most likely explanation because 50% of acute hemorrhagic stroke cases can be attributed to hypertension in Chinese.21

Few community-based studies on ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke subtypes were identified. In the recent multicenter study on the prevalence and outcomes of intracranial large artery atherosclerosis among patients with stroke and transient ischemic attack in China (the Chinese Intracranial Atherosclerosis Study), the prevalence of intracranial stenosis was 46.6% (1,335 patients, including 261 with coexisting extracranial carotid stenosis).22 In addition, geographic and sex differences were noted in the distribution of symptomatic intracranial atherosclerosis cases in China. The proportion of patients with intracranial atherosclerosis was significantly higher in Northern than in Southern China (50.22% vs. 41.88%; P<0.0001). The patients from Northern China were likely to consume more alcohol and cigarettes, and a significantly higher proportion of whom had diabetes mellitus; family histories of stroke, cerebral ischemia, and heart disease; and higher BMI (in press).23

Geographical variation

There are substantial geographic disparities in stroke incidence, mortality, and prevalence worldwide. Higher stroke rates in the Southeastern United States (the so-called Stroke Belt), especially along the coasts of Georgia and the Carolinas (socalled Stroke Buckle),24 are well known. In China, all stroke epidemiological studies also suggested a marked geographical variation. Northeastern China has the highest incidence (441-486 cases per 100,000 population per year), whereas Southern China has a significantly lower incidence (81-136 cases per 100,000 population per year).5,8,10 Studies suggested the north-south gradient, with the highest incidence rate in the Heilongjiang province and the lowest incidence rates in the Zhejiang and Guangxi provinces. The Heilongjiang province has 6 times higher stroke incidence rate and 9 times higher mortality rate than the Guangxi province.8 The geographical variation in stroke incidence and mortality may be mainly due to differences in the prevalence of hypertension, the most important risk factor of stroke. The stroke population attributed to hypertension is as great as 40%.

Risk factors

With the economic growth, the Chinese lifestyle has rapidly changed in the past 3 decades. The risk from major stroke factors, including obesity and hypercholesterolemia, has substantially increased. For example, total fat intake increased from 88.1 g/day in 1983 to 97.4 g/day in 2002. During the same period, total cholesterol intake increased from 124.8 to 350.7 g/day in rural areas and from 334.5 to 488.4 g/day in urban areas.25,26 From 1984 to 1999, mean blood cholesterol level increased by 24%.27 From 1994 to 2002, diabetes prevalence increased by 97%, and overweight or obesity prevalence increased by 85% in the rural areas and 13% in the urban areas.21

At present, the incidence of risk factors for cardiovascular disease and stroke in China has become similar to that in the Western countries, including hypertension, diabetes, hypercholesterolemia, smoking, coronary artery disease, arterial fibrillation, physical inactivity, and obesity. Among the modifiable risk factors, hypertension remains to be the most important risk factor for all types of strokes, with the highest population-attributable risk at 34.6%.

The control rate of hypertension differs between the urban and rural areas: In urban areas, it was 3.4% in 1984 and significantly increased to 17.5% in 1999, whereas in rural areas, it did not change much (1.1% in 1984 and 6.9% in 1999).28

Intracranial atherosclerotic disease is more prevalent in the Chinese population than in Western populations. Recent Chinese Intracranial Atherosclerosis Study data suggest that patients with intracranial stenosis had more severe stroke at admission and longer hospital stay than those without intracranial stenosis (median National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale score, 5 vs. 3; median length of hospital stay, 16 vs. 14 days). At 12 months, stroke recurred in 3.24% of all patients with no stenosis, 3.82% of 50-69% of patients with stenosis, 5.16% of 70-99% of patients with stenosis, and 7.40% of 100% of patients with occlusion (in press).22

Ongoing epidemiological survey and future direction

Epidemiological studies can help identify groups of individuals or regions at higher risk of stroke. They can also help better understand the natural history of certain associated conditions and therefore push the direction of prevention and therapeutic investigations. However, the most widely cited data on the incidence, prevalence, and mortality of stroke are derived from the studies carried out in the 1980s. Stoke epidemiological features in China have changed with the economic development in the last 3 decades. It is important to understand these changes to establish timely strategies for stroke prevention.

To aim at revealing the characteristics of stroke transition, the China Nationwide Epidemiological Survey for cerebrovascular disease will be implemented in 2013. This survey is one of the National Key Technology R&D Programs during the "Twelve-Fifth Plan" period (grant no. 2011BAI08B01). The main purpose of the survey is to obtain the incidence, prevalence, and mortality of stroke in different regions of China; the secondary purpose is to access relevant data on stroke and transient ischemic attack, including risk factors, treatment, and secondary prevention. The epidemiological survey will conducted in 150-160 disease surveillance points, which come from the National Disease Surveillance System in 31 provinces (municipal cities) in China. A multistage stratified cluster sampling method will be applied to obtain the sample population. The total sample size is expected to be more than 600,000 patients. The survey will be completed in cooperation of staffs from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and neurologists in each province. The results of this survey are eagerly anticipated.

Future epidemiological studies on stroke in China should use high-quality methods to update our understanding on the incidence (first and recurrent events), prevalence, mortality, cost, and specific characteristics of stroke (ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke subtypes, small vessel disease, etc.). Nationwide hospital-based and especially community-based stroke registers are required to monitor stroke incidence and trends, as well as the quality of stroke care. Feasible and affordable long-term primary and secondary prevention strategies should be developed and strongly recommended for clinical settings. Complementary alternative therapeutics such as traditional Chinese medicine, acupuncture, urokinase, snake venom, and hematoma aspiration for intracerebral hemorrhage should be assessed by means of internationally recognized methods.29

Support from the Chinese government

Prevention remains to be the most viable avenue for lessening the burden of stroke on society, considering the high incidence of stroke worldwide, insidious contribution of stroke risk factors, and the paucity of proven acute stroke therapies. Despite the challenges and amount of work, the Chinese people are giving an organized effort to provide better stroke care. A comprehensive plan to address this issue and improve stroke care has been developed. The Ministry of Health has just established the Chinese National Center for Stroke Care Quality Control and Management. A national stroke data bank is being established based on the blueprint of the Chinese National Stroke Registry. Extensive physician training and community education on evidence-based stroke care have been incorporated into the "Twelve-Fifth Year project."30 As the world has witnessed the impressive economic growth in China in the past 3 decades, we expect substantial improvement in stroke care.

Notes

This survey is supported by the National Key Technology R&D Programs during the "Twelve-Fifth Plan" period (grant no. 2011BAI08B01).

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest.