Isolated Vascular Vertigo

Article information

Abstract

Strokes in the distribution of the posterior circulation may present with vertigo, imbalance, and nystagmus. Although the vertigo due to a posterior circulation stroke is usually associated with other neurologic symptoms or signs, small infarcts involving the cerebellum or brainstem can develop vertigo without other localizing symptoms. Approximately 11% of the patients with an isolated cerebellar infarction present with isolated vertigo, nystagmus, and postural unsteadiness mimicking acute peripheral vestibular disorders. The head impulse test can differentiate acute isolated vertigo associated with cerebellar strokes (particularly within the territory of the posterior inferior cerebellar artery) from more benign disorders involving the inner ear. Acute audiovestibular loss may herald impending infarction in the territory of anterior inferior cerebellar artery. Appropriate bedside evaluation is superior to MRIs for detecting central vascular vertigo syndromes. This article reviews the keys to diagnosis of acute isolated vertigo syndrome due to posterior circulation strokes involving the brainstem and cerebellum.

Introduction

Approximately, 20% of ischemic events occur in the territory of the posterior (vertebrobasilar) circulation, and dizziness/vertigo is one of the most common symptoms of vertebrobasilar diseases.1 With the aids of recent development in neuroimaging, however, inferior cerebellar and small brainstem infarctions are increasingly recognized as a cause of isolated vertigo. Furthermore, transient isolated vertigo is the common manifestation of vertebrobasilar insufficiency.2

It is important to differentiate isolated vertigo of a vascular cause from more benign disorders involving the inner ear since the therapeutic strategy and prognosis differ in these two conditions.3 Early recognition of isolated vertigo of a vascular cause may allow specific management. Misdiagnosis of acute stroke may result in significant morbidity and mortality while overdiagnosis of vascular vertigo would lead to unnecessary costly work-ups and medication.3 This review aims to highlight advances in isolated vertigo of a vascular cause and to address its clinical significance.

Recurrent episodes of isolated vertigo of a vascular cause

In cerebrovascular disorders, the dizziness/vertigo usually accompanies other neurological symptoms and signs. Indeed, medical adage had taught us that isolated vertigo mostly comes from peripheral vestibular diseases. However, isolated vascular vertigo might have been underestimated. Diagnosis of isolated vertigo from brainstem and cerebellar strokes has been increasing markedly with recent developments in clinical neurotology and neuroimaging.3

Transient isolated vascular vertigo typically occurs abruptly, and usually lasts several minutes. In patients with vertigo due to vertebrobasilar insufficiency, 62% had a history of at least one isolated episode of vertigo, and 19% developed vertigo as the initial symptom.2 Patients with infarction in the territory of anterior inferior cerebellar artery (AICA) may have isolated recurrent vertigo, fluctuating hearing loss, and/or tinnitus (similar to Meniere's disease) as the initial symptoms 1-10 days prior to the permanent infarction.4

A recent study found that the patients who visited the emergency department with dizziness/vertigo had 2-fold (95% CI, 1.35-2.96; P<0.001) higher risk of stroke or cardiovascular events than those without dizziness/vertigo during a follow-up of 3 years.5 The authors also demonstrated that the patients hospitalized with isolated vertigo have a 3.01-times (95% CI, 2.20-4.11; P<0.001) higher risk for stroke than the general population during the 4-year follow-up.5 Particularly, the vertigo patients with 3 or more risk factors have a 5.51-fold higher risk for stroke (95% CI, 3.10-9.79; P<0.001) than those without risk factors.5 Another study adopted the ABCD2 score,6 a clinical prediction tool to assess the risk of stroke after a transient ischemic attack, to predict cerebrovascular events in emergency department patients with dizziness.7 The authors found that only 1.0% of dizzy patients with a score of 3 or less had a cerebrovascular event compared to 8.1% of the patients with a score of 4 or more.7 Especially, 27% of the patients with a score of 6 or 7 suffered from cerebrovascular episodes.7 Thus, the ABCD2 score may predict cerebrovascular attacks in patients with transient vertigo. All of these data suggest that isolated episodic vertigo with or without auditory symptoms may be the only manifestation of transient ischemia within the vertebrobasilar circulation.

Labyrinthine infarction

Because the blood supply to the inner ear originates from the vertebrobasilar system, vertebrobasilar ischemic stroke can present with vertigo and hearing loss due to infarction of the inner ear (i.e., labyrinthine infarction).

The internal auditory artery (IAA) is a branch of AICA. The IAA irrigates the cochlea and vestibular labyrinth, and occlusion of the IAA causes loss of auditory and vestibular function. Since the IAA is an end artery with minimal collaterals from the otic capsule, the labyrinth is especially vulnerable to ischemia.2,8 IAA infarction mostly occurs due to thrombotic narrowing of the AICA itself, or in the basilar artery at the orifice of the AICA.9

Because the inner ear is hardly visualized on the routine MRIs, a definite diagnosis of labyrinthine infarction is not possible unless a pathological study is done.10 The apical region of the cochlea is particularly vulnerable to vascular injury, and, thus, low-frequency hearing loss is common with ischemia of the inner ear.11 However, a labyrinthine infarction is usually associated with infarction of the brainstem and/or cerebellum in the territory of the AICA.12

The labyrinthine infarction should be considered in older patients with acute onset of unilateral hearing loss and vertigo, particularly when there is a history of stroke or known vascular risk factors. Because current means of diagnosing labyrinthine infarction are not adequate (including MRIs), clinicians should consider all the clinical evidences when attempting to determine the etiology of acute audio-vestibular syndromes rather than just emphasizing that MRI is the best way to distinguish viral from vascular etiology.13

Anatomical structures responsible for central isolated vertigo of a vascular cause

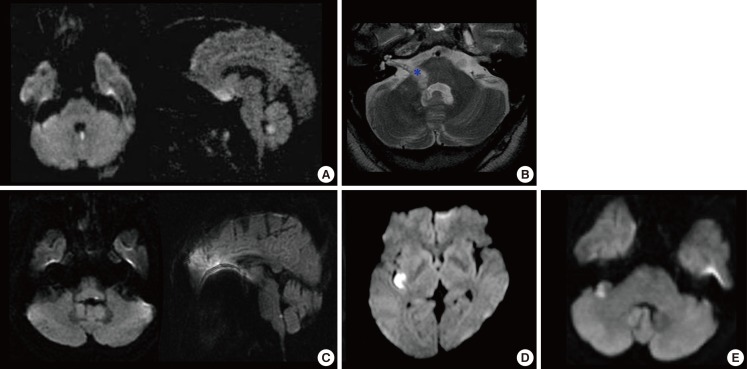

Vertigo results from imbalance in the tonic discharges of the vestibular system arising from the inner ears on both sides. The origin of vertigo may be peripheral or central. When the vertigo occurs as a symptom of vertebrobasilar ischemic strokes, it is usually associated with other neurological symptoms or signs. Theoretically, a small infarct localized to structures such as the nodulus, root entry zone of the eighth nerve in the pontomedullary junction, and vestibular nucleus can cause vertigo without other accompanying neurological symptoms or signs since all of these structures receive afferent vestibular inputs from the inner ear (Figure 1). Because the vestibular nucleus is more vulnerable to ischemia than other structures in the brainstem and cerebellum from a recent animal study,14 ischemia of the lateral medulla including the vestibular nucleus may be a common mechanism of isolated vascular vertigo. Rarely, lesions involving the flocculus or dorsal insular cortex can also cause isolated vertigo (Figure 1).15,16,17 Vertigo due to a lesion involving the dorsal insular cortex is usually not associated with nystagmus and a flocculus lesion is commonly associated with other central signs such as gaze-evoked nystagmus (GEN) and asymmetrical oculomotor dysfunction.15,16,17

Focal infarction selectively involving the structures responsible for isolated vertigo. (A) Isolated nodulus infarction. (B) Anterior inferior cerebellar artery territory infarct involving the lateral caudal pons extending from the root entry zone (*) of the eighth nerve to the most proximal portion of the vestibular fascicle. (C) Isolated vestibular nucleus infarction. (D) Focal infarction selectively involving the dorsal insula. (E) The flocculus is selectively infracted (from Lee [42], with permission).

Bedside diagnosis of stroke in acute isolated vertigo

Because central vestibular signs such as vertical nystagmus, direction changing GEN, perverted head shaking nystagmus (HSN), asymmetrical oculomotor dysfunction, or severe postural instability with falling do not appear in all patients with central vertigo, it is not always easy to differentiate isolated vascular vertigo from acute peripheral vestibulopathy at the bedside. Most of these signs are known to have a high specificity, but low sensitivity for detecting a central cause of acute isolated vertigo.

It is well believed that the bedside head impulse test (HIT) is a useful tool for differentiating acute vascular vertigo from a more benign disorder involving the inner ear. Normal HIT is regarded a reliable sign for an intact peripheral vestibular function, thus suggesting a central lesion in acute spontaneous vertigo. The significance of HIT for differentiating stroke from acute peripheral vestibulopathy has been confirmed in a recent study18 which showed that a negative HIT result (i.e., normal vestibulo-ocular reflex) is strongly suggestive of a central lesion with a pseudo-VN presentation. The study emphasized that a 3-step bedside oculomotor examination for HINTS (normal HIT, direction-changing GEN, and skew deviation) is more sensitive for stroke than early MRI whilst maintaining a high specificity.18 Indeed, initial diffusion-weighted MRIs may be false negative in 12%-20% of the stroke patients during the first 48 hours.18,19 Another recent report also confirmed diagnostic utility of the signs including normal horizontal HIT, skew deviation, abnormal vertical smooth pursuit, and central type nystagmus at the bedside: they found a 100% sensitivity and 90% specificity for stroke if one of those signs was present in acute isolated vertigo.20 Since mild degree of skew deviation usually goes unnoticed during the bedside examination and GEN is also sometimes absent in cerebellar stroke, bedside HIT may be the best tool for differentiating isolated vertigo due to cerebellar stroke (particularly within the territory of the posterior inferior cerebellar artery, PICA) from acute peripheral vestibulopathy. However, bedside HIT has some limitations, and may be positive in patients with AICA territory cerebellar infarct involving the flocculus, or brainstem stroke involving the vestibular nucleus or root entry zone of the vestibular nerve.18,21,22,23

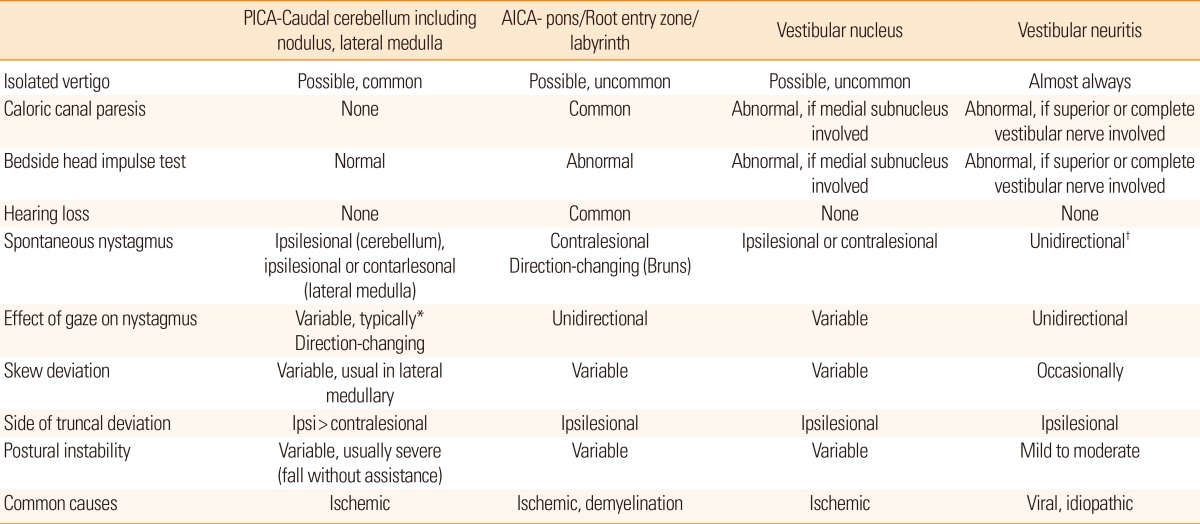

Overall, the most consistent bedside predictor of central isolated vertigo of a vascular cause appears to be the HIT and normal HIT usually guarantees an absence of peripheral pathology. A three-component bedside oculomotor examination (i.e., HINTS) identifies stroke with high sensitivity and specificity in patients with acute isolated vertigo and diagnoses stroke more effectively than early diffusion-weighted MRIs. Differential diagnostic points for central and peripheral acute vertigo syndromes are summarized in Table 1.

Isolated vertigo in cerebellar stroke

Dizziness/vertigo is one of the most common symptoms of cerebellar stroke syndrome. Cerebellar ischemic stroke probably ranks first among central vascular vertigo syndromes. A large prospective study showed that about 11% (25/240) of the patients with isolated cerebellar infarctions had isolated vertigo and most (24/25, 96%) of them had an infarct in the territory of the medial branch of the PICA including the nodulus.24

In PICA territory cerebellar infarction, the direction of nystagmus and degree of postural instability are variable. The prominent cerebellar signs, particularly severe axial instability and direction changing GEN (occurring in 71% and 54%, respectively, in the aforementioned series),24 can help in the differential, but these findings are less sensitive. Similarly, perverted head shaking (mostly down beating) and positional down beating nystagmus as important signs of central vestibular dysfunctions are found in only half of the cases with cerebellar infarction.25 Overall, although the severity of imbalance and the appearance of nystagmus in PICA territory cerebellar infarctions can help in differentiating acute vertigo syndrome from vertigo originating from the inner ear, these findings are less sensitive for differentiating two conditions. PICA territory cerebellar infarction should be considered in the differential diagnosis of central vascular vertigo syndrome, even if the nystagmus and imbalance are more typical of acute vertigo originating from the inner ear.

GEN is a sensitive sign of central vestibular lesions involving the cerebellum or brainstem. A recent study showed that unidirectional GEN was found in 33% of the patients with acute unilateral cerebellar stroke and the nystagmus was directed either toward or away from the lesion side.26 The structures responsible for unidirectional GEN included the pyramid, uvula, tonsil, and parts of the biventer and inferior semilunar lobules.26 GEN may be a sign indicating damage to the midline and lower cerebellar structures. Of interest, however, none of the patients showed spontaneous nystagmus and none of the patients with GEN had a lesion in the flocculus, which is known to play a major role in the gaze holding mechanism.

Another study25 found that 51% of patients (37/72) with isolated cerebellar infarction showed HSN and the horizontal component of HSN was constantly ipsilesional. Perverted HSN occurred in 23 (23/37, 62%) patients and was mostly downbeat (22/23, 96%). Lesion subtraction analyses revealed that damage to the uvula, nodulus and inferior tonsil was mostly responsible for generation of HSN in patients with unilateral PICA territory infarction. The authors argued that ipsilesional HSN may be caused by unilateral disruption of uvulonodular inhibition over the velocity storage. Otherwise, the perverted HSN may be ascribed to impaired control over the spatial orientation of the angular vestibulo-ocular reflex due to uvulonodular lesions or a build-up of vertical vestibular asymmetry favoring upward bias due to lesions involving the inferior tonsil.25 In AICA infarction, HSN is also common with both peripheral and central patterns. Careful evaluation of HSN may provide clues for AICA infarction in patients with acute audiovestibular loss.27 Another study28 on long-term outcome of vestibular loss of a vascular cause showed that the caloric responses were normalized in 70% (20/30) of the patients who had canal paresis due to posterior circulation ischemic strokes and had a follow-up for at least 1 year. Moreover, all patients who were followed for >5 years after the onset of vertigo showed normal caloric responses, suggesting that, like other neurological symptoms or signs due to stroke, canal paresis associated with posterior circulation ischemic strokes has a good long-term outcome although the detailed mechanism underlying the recovery of caloric-induced vestibular responses still unclear. Another study29 on the long-term outcome of acute hearing loss reported a similar finding that approximately 65% of the patients who were followed for at least 1 year after the onset of acute hearing loss showed a partial or complete hearing recovery. Multivariate analysis showed that multiple risk factors for stroke (odds ratio [OR], 10.46; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.72 to 13.7; P=0.011) and profound hearing loss (OR, 3.92; 95% CI, 1.03 to 14.97; P<0.046) predicted a poor outcome for recovery of hearing loss. The a bove two reports suggest that recovery of audiovestibular loss of a vascular cause is more common than previously thought.

To date, at least eight subgroups of AICA infarction have been identified according to the patterns of neurotological presentations, among which the most common pattern of audiovestibular dysfunction is the combined loss of auditory and vestibular functions.30,31 Because audiovestibular loss may occur in isolation before ponto-cerebellar infarction involving AICA distribution, audiovestibular loss may herald more widespread areas of infarction involving the posterior circulation (mainly in the AICA territory),30,31 especially when patients had basilar artery occlusive diseases presumably close to the origin of the AICA on brain MRA, even if other central signs are absent and MRI does not demonstrate acute infarction.30,31

In a recent study of isolated superior cerebellar artery (SCA) territory cerebellar infarction, approximately half (19/41) of the patients experienced true vertigo and 11 (27%) showed spontaneous nystagmus mainly beating to the lesion side or GEN.32 The authors emphasized that the vertigo and nystagmus in the SCA territory cerebellar infarctions are more common than previously thought. Ipsilesional spontaneous nystgmus may result from damage to the anterior lobe of the cerebellum, which transmits the vestibular output to the fastigial nucleus.32

Isolated vertigo in brainstem stroke

Mono-symptomatic attacks of vertigo and nystagmus without any other brainstem symptoms and signs would be unusual in brainstem ischemia. Selective damage to the vestibular nuclei and root entry zone of the eighth nerve in the pontomedullary junction can cause isolated vertigo.33,34,35,36,37 Because the root entry zone of the eighth cranial nerve has a rich network of anastomotic vessels arising from the neighboring arteries,38 the possibility of focal infarction in that area is extremely low. Although some case reports showed central isolated vertigo due to a demyelinating lesion localized to the root entry zone of the eighth nerve,33,34 isolated vertigo due to focal infarction in the root entry zone of the vestibular nerve has not been reported in the literature. Focal ischemia involving the vestibular nuclei can cause isolated vertigo and nystagmus mimicking acute vestibular neuritis.35,36,37 Several studies have described patients with an isolated vestibular nucleus infarction who presented with isolated prolonged vertigo, spontaneous horizontal nystagmus, a positive HIT, and unilateral canal paresis.35,36,37 All of these findings are consistent with acute peripheral vestibulopathy. These reports emphasize that isolated vestibular nucleus infarction should be considered in the differential diagnosis of central vascular vertigo syndrome, even though when the patients have unilateral canal paresis and positive HIT on the side of the canal paresis, and other neurologic symptoms or signs are absent. Vertigo in the lateral medullary infarction is usually associated with other neurological symptoms or signs, but tiny infarct in the lateral medulla can present with vertigo without other localizing symptoms.39 In this case, the HIT might be positive, if the medial vestibular nucleus is involved. Vestibular-evoked myogenic potentials (VEMPs) have become important diagnostic tools to assess the central otolithic pathways in brainstem and cerebellar lesions. Recent reports on VEMPs in patients with brainstem infarcts showed a various pattern of abnormal VEMPs responses.40,41

Isolated vertigo and/or hearing loss as a sign of impending AICA territory cerebellar infarction

Recent papers have shown that 8%-30% of patients with posterior circulation ischemic strokes (mainly in the AICA territory) had acute audiovestibular loss with vertigo, fluctuating hearing loss and/or tinnitus before more widespread infarction and at this stage, patients may be misdiagnosed as having a peripheral pathology such as Meniere's disease.30,43,44 Selective ischemia to the inner ear can explain the isolated prodromal audiovestibular disturbance because the inner ear requires high-energy metabolism and has little collateral circulation.30,42,43 Although there are as yet no systematic data on which are the high-risk factors suggesting impending stroke or which interventions are beneficial at the stage of isolated audiovestibular loss, patients with a prodromal audiovestibular disturbance are more likely to have a focal or diffuse stenosis of the basilar artery presumably close to the origin of the AICA than the patients without a prodromal audiovestibular disturbance.4,12,30,43,44 This finding highlights that AICA infarction should be considered, particularly in elderly patients with vascular risk factors and acute audiovestibular loss, even when MRI does not demonstrate acute infarction in the brain. At this stage, clinicians should consider a further investigation and a proper management to prevent progression of acute audiovestibular loss into a more widespread posterior circulation stroke, mainly in the territory of AICA.31

When does the patient with isolated vertigo need an urgent brain scan and what role does neuroimaging play in diagnosis?

For patients with spontaneous prolonged vertigo, in addition to obvious cases of associated neurological symptoms or signs, an urgent brain scan should be considered to rule out central vascular vertigo syndrome in 1) older patients presenting with isolated spontaneous prolonged vertigo, in 2) any patient with vascular risk factors and isolated spontaneous prolonged vertigo who had a normal HIT, in 3) any patient with isolated spontaneous prolonged vertigo who had direction changing GEN or severe gait ataxia with falling at upright posture, in 4) any patient presenting with acute spontaneous vertigo and new onset headache, especially occipital, and in 5) any patient with vascular risk factors and acute onset of vertigo and hearing loss without a history of Meniere's disease.24,42 Since brain CT is known less accurate in detecting an acute ischemic lesion within the posterior fossa,45 brain MRIs with diffusion imaging are considered the golden standard for diagnosis of isolated vertigo due to ischemic strokes. However, diffusion-weighted MRI can be misleading up to at least 48 hours after onset of vertigo due to a stroke. Recent systemic review showed that the aggregate sensitivity of diffusion-weighted MRI of the posterior fossa during the first 24 hours or so after the vertigo onset to be 80% and a negative likelihood ration of 0.21 (95% CI, 0.16-0.26), which makes MRIs less potent for diagnosing stroke than the composite HINTS examination.19

Conclusion

Patients with isolated vertigo are at a higher risk for stroke than the general population. Stroke in the distribution of the posterior circulation may mimic acute peripheral vestibular disorders. Isolated acute audiovestibular loss may herald an impending AICA territory infarction. A focused bedside examination (i.e., HINTS) identifies stroke with high sensitivity and specificity in patients with acute isolated vertigo and is superior to diffusion-weighted MRIs during the acute phase.

Notes

The author has no financial conflicts of interest.

Dr. Lee serves on the editorial boards of the Research in Vestibular Science, Frontiers in Neuro-otology, and Current Medical Imaging Review.