|

|

- Search

| J Stroke > Volume 25(1); 2023 > Article |

|

Cerebral infarction may lead to delayed neuronal degeneration in remote areas of the brain that are connected to the primary ischemic lesion [1]. Particularly, basal ganglia infarctions may be associated with delayed degeneration of the substantia nigra (SN) [2,3]. Although delayed SN degeneration is often observed on diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) in patients with stroke [2-5], the factors associated with delayed SN degeneration and its clinical significance are unclear. Herein, we investigated factors associated with delayed SN degeneration in patients with acute infarction involving the basal ganglia. We also investigated the short-term neurological outcomes.

This was a retrospective study using data from the Effects of Very Early Use of Rosuvastatin in Preventing Recurrence of Ischemic Stroke (EUREKA) trial [6]. We used these data because they included initial (within 48 hours after onset) and follow-up DWI data at days 5 and 14 with National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) scores. This study included patients who had an infarction involving the unilateral basal ganglia on initial DWI and who underwent follow-up DWI at least once at day 5 or 14. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Severance Hospital, Yonsei University Health System (no. 4-2021-1272), which waived the need for informed consent owing to the study’s retrospective design. Images were analyzed to determine the location of ischemic lesions in the basal ganglia and co-existing lesions in the territory of the middle cerebral artery (MCA). The volume of ischemic lesions in the basal ganglia was measured semi-automatically using Xelis software (Infinitt, Seoul, Korea) [7]. The occurrence of SN degeneration was determined on follow-up DWI at days 5 and 14. SN degeneration was defined as a lesion with high signal intensity in the SN region on DWI (Supplementary Figure 1). Images were independently analyzed by two investigators (K.L. and J.H.H.), and any discrepancies were resolved by consensus. We compared the degree of neurological improvement based on the percent improvement in NIHSS scores between patients with and without SN degeneration. The percent improvement was defined as [(NIHSS at baseline - NIHSS at 14 days) / NIHSS at baseline × 100] [6]. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software for Windows version 23.0 (IBM Co., Armonk, NY, USA). All statistical analyses were two-tailed, and statistical significance was set at P<0.05. Details of the statistical analyses are described in the Supplementary Methods.

Of the 318 patients enrolled in the EUREKA trial, 289 who underwent follow-up DWI at least once were considered. We excluded two patients who underwent stent insertion because this might have affected the development of new lesions on follow-up DWI. Of the remaining 287 patients, this study finally included 62 patients who had lesions in the basal ganglia. Thirty-one patients (50%) had co-existing lesions in the MCA territory (Supplementary Figure 2). Lesions in the SN were detected in 27 patients (43.5%) on follow-up DWI (10 [16.1%] at 5 days and 27 [43.5%] at 14 days).

Patients with SN degeneration had significantly lower blood uric acid levels (0.27±0.11 vs. 0.33±0.10, P=0.043) than those of patients without SN degeneration (Supplementary Table 1). Co-existing infarctions in the MCA territory were more frequent in patients with SN degeneration (66.7% vs. 37.1%, P=0.021). The infarction volume in the basal ganglia was significantly larger in patients with SN degeneration (1.5 [interquartile range, IQR, 0.5 to 4.6] vs. 0.7 [IQR, 0.2 to 1.4], P=0.02) (Supplementary Table 2). On multivariable analysis, SN degeneration was significantly associated with co-existing infarctions in the MCA territory (adjusted odds ratio [OR], 4.118; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.225 to 13.843; P=0.022) and the infarction volume in the basal ganglia (adjusted OR, 1.379; 95% CI, 1.050 to 1.813; P=0.021) (Table 1).

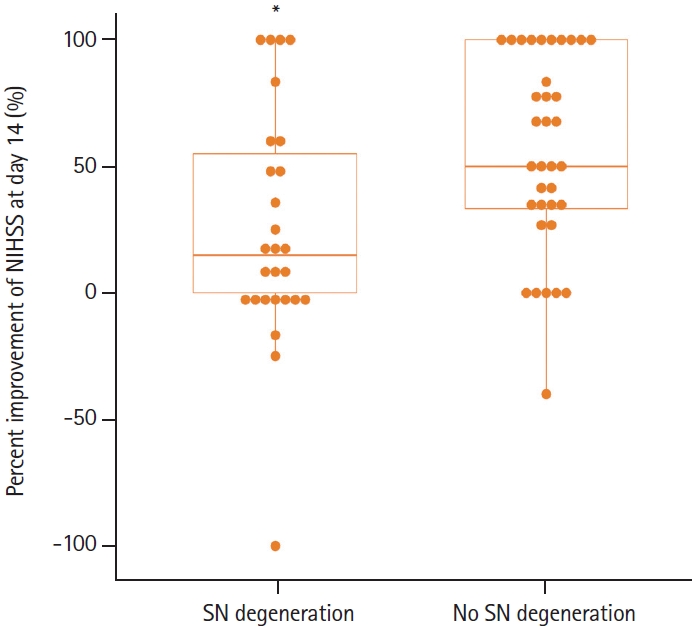

The initial NIHSS score was significantly higher in patients with SN degeneration (median, 8; IQR, 4 to 14) than in those without SN degeneration (median, 4; IQR, 2 to 6) (P=0.001). The percent improvement in the NIHSS score at 14 days was significantly lower in patients with SN degeneration (median, 15%; IQR, 0% to 60%) than in those without SN degeneration (median, 50%; IQR, 33.3% to 100%) (P=0.04) (Figure 1). On univariable and multivariable linear regression analyses, SN degeneration was independently associated with percent improvement (P=0.016) (Table 2).

This study showed that SN degeneration was observed on DWI in approximately 44% of patients with basal ganglia infarctions within 2 weeks, and the occurrence of SN degeneration was associated with the infarction volume in the basal ganglia and co-existing infarction in the MCA territory. Our findings are supported by those of a previous autopsy study, which showed SN degeneration in patients with massive basal ganglia infarctions but not in those with smaller infarctions [8]. Large infarctions may produce greater involvement of striatonigral fibers, which increases the likelihood of visible changes on DWI by increasing the extent or severity of SN degeneration. In this study, co-existing MCA infarctions were also associated with SN degeneration. Previous studies did not identify SN degeneration in patients with infarctions in the cerebral cortex of the MCA territory without striatal lesions [3,4]. However, in a recent study of a stroke model with isolated cortical infarction in rats, the loss of dopaminergic neurons in the midbrain occurred 14 days after stroke [9]. These findings suggest that polysynaptic coupling may play a role in delayed exo-focal post-ischemic neurodegeneration [9].

This study showed that patients with SN degeneration had worse neurological deficits than those without SN degeneration. Our findings suggest that SN degeneration may negatively affect recovery from neurological deficits and that prevention of SN degeneration is a potential therapeutic target [10]. Inflammation may play a key role in the development of delayed neuronal degeneration in remote brain areas [5,7].

In conclusion, SN degeneration is associated with large infarctions involving the basal ganglia and co-existing infarctions involving the MCA territory. Patients with SN degeneration showed less improvement in their neurological deficits during the acute phase of stroke. Further studies involving long-term follow-up DWIs with analyses of clinical outcomes in a larger patient cohort are warranted.

Supplementary materials

Supplementary materials related to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.5853/jos.2022.02145.

Supplementary Figure 1.

Representative diffusion-weighted images showing the degeneration of the substantia nigra in the midbrain (arrows).

Supplementary Figure 2.

Patient flow diagram. EUREKA, Effects of Very Early Use of Rosuvastatin in Preventing Recurrence of Ischemic Stroke; DWI, diffusion- weighted imaging; MCA, middle cerebral artery; SN, substantia nigra.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health grants R01NS095359, NS103326, and NS111568 (SC).

We thank the EUREKA trial investigators.

Figure 1.

Percent improvement in National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) scores on day 14 after stroke. Patients with substantia nigra (SN) degeneration showed less neurological improvement. *P=0.04.

Table 1.

Factors associated with the occurrence of substantia nigra degeneration

Table 2.

Factors associated with the percent improvement in NIHSS scores

References

1. Rodriguez-Grande B, Blackabey V, Gittens B, Pinteaux E, Denes A. Loss of substance P and inflammation precede delayed neurodegeneration in the substantia nigra after cerebral ischemia. Brain Behav Immun 2013;29:51-61.

2. Nakajima M, Inatomi Y, Okigawa T, Yonehara T, Hirano T. Secondary signal change and an apparent diffusion coefficient decrease of the substantia nigra after striatal infarction. Stroke 2013;44:213-216.

3. Ogawa T, Okudera T, Inugami A, Noguchi K, Kado H, Yoshida Y, et al. Degeneration of the ipsilateral substantia nigra after striatal infarction: evaluation with MR imaging. Radiology 1997;204:847-851.

4. Winter B, Brunecker P, Fiebach JB, Jungehulsing GJ, Kronenberg G, Endres M. Striatal infarction elicits secondary extrafocal MRI changes in ipsilateral substantia nigra. PLoS One 2015;10:e0136483.

5. Park KW, Ju H, Kim ID, Cave JW, Guo Y, Wang W, et al. Delayed infiltration of peripheral monocyte contributes to phagocytosis and transneuronal degeneration in chronic stroke. Stroke 2022;53:2377-2388.

6. Heo JH, Song D, Nam HS, Kim EY, Kim YD, Lee KY, et al. Effect and safety of rosuvastatin in acute ischemic stroke. J Stroke 2016;18:87-95.

7. Yoo J, Baek JH, Park H, Song D, Kim K, Hwang IG, et al. Thrombus volume as a predictor of nonrecanalization after intravenous thrombolysis in acute stroke. Stroke 2018;49:2108-2115.

8. Forno LS. Reaction of the substantia nigra to massive basal ganglia infarction. Acta Neuropathol 1983;62:96-102.